An Open Letter to my Son About the Music that Shaped my Life

dear harrison,

As a person who has been passionate about music for almost four decades, I have endeavored to narrow down a list of those artists who have made the biggest impact on me. The nature of creating a list - that is having to choose whom to include and exclude - is in itself a revealing act which causes me to reflect upon my values, upbringing, and how my environment informs the ongoing development of my personality. More importantly, it forced me to reflect upon the lessons I have learned, in addition to the pure joy I have experienced, through my relationship with music.

A person can reflect upon one’s life through many lenses - family, finances, religious views, etc. In my experience, art has always been both experiential and aesthetic. Yes, I listen to music to enjoy it, but there are other levels that I experience music on. The experience of listening can prompt me to evolve my perspective, open myself to different experiences or values, or have different impressions upon my mind that cause a visceral or emotional response. For example, when I was 13, I remember my family making the drive to drop your Aunt Sarah, who is 5 years my senior, off to college for the first time. I was listening to Led Zeppelin II on my walkman, one of my favorite albums at the time. Every time I listen to it, I am transported back to that day. Perhaps, it is more accurate to say that it evokes certain impressions from that day - what it felt like to be 13, sitting in the back seat of a hot car on a sunny day, apprehensive about my sister moving out of the house but excited for her to begin her new life.

Bearing this in mind, I have undertaken the task of ranking the two dozen musical artists who had the biggest impact on my life. More importantly, I will sum up what each artist has meant to me in the form of a lesson - a small sliver of wisdom to impart to you. The real lesson, though, is that I want you to be open to learning, in all its forms. Be curious about an author, try a new food, ask somebody where they grew up and what it was like there. As I said, music tends to evoke powerful impressions in my mind, but really, anything can accomplish this, and your unique experience will mold itself around your interests, likes and dislikes, values, and so on. These just happen to be mine.

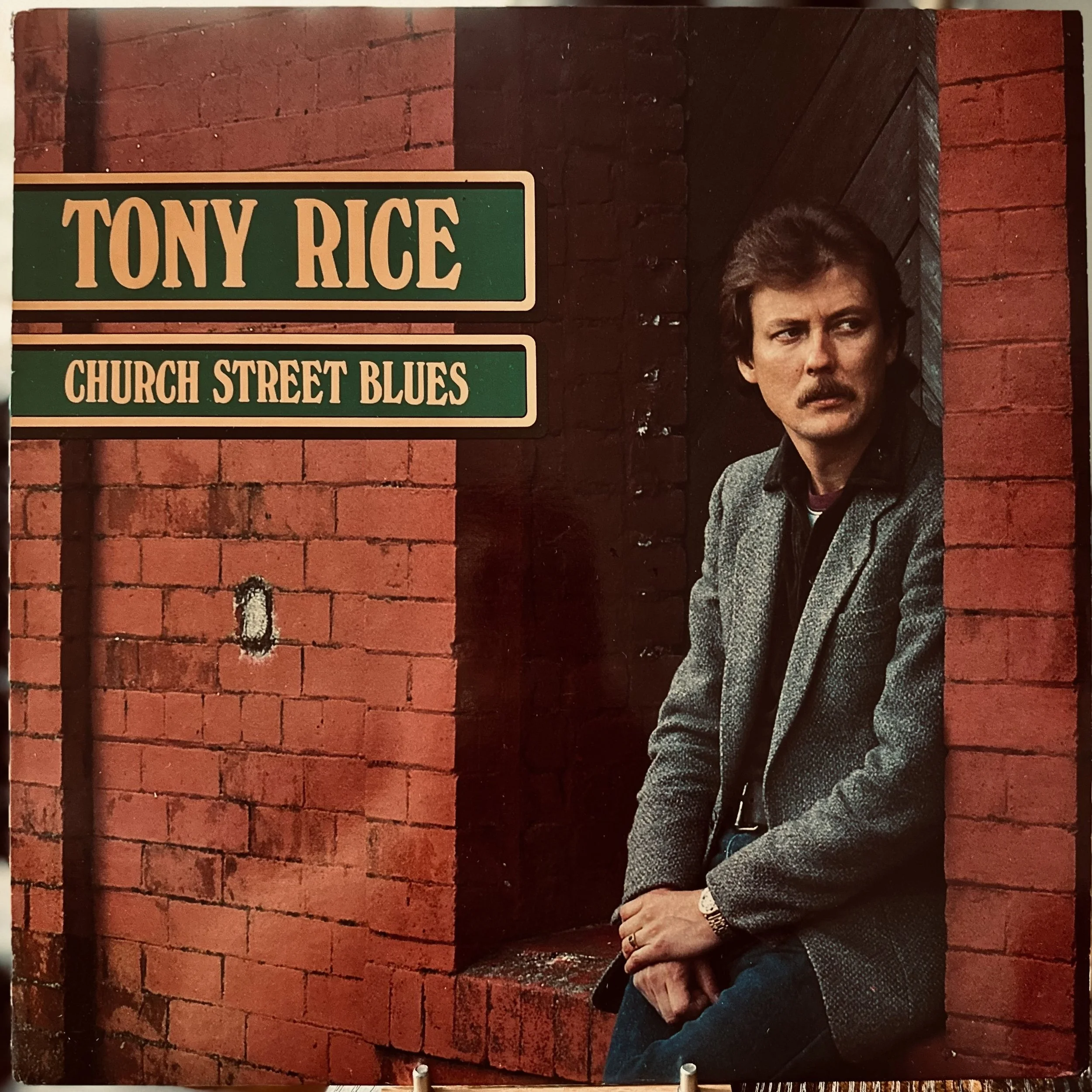

24. Tony Rice

Tony Rice was one of the most gifted guitarists who ever lived. He played bluegrass guitar with speed and expression that seemed almost superhuman. What stands out to me about his playing is that he studied jazz guitar and used this style to inform his bluegrass playing at a level that was unattainable by most others.

While it may not seem obvious on the surface, there is a lot of similarity between jazz and bluegrass. The idea of stating a melody, and then using it to improvise extensively, especially in a group setting, is common to both, but Tony Rice, along with David Grisman, pioneered the use of jazz scales and rhythms is a bluegrass context that blurred the lines between the two genres. He also played very traditional bluegrass and folk, singing with a sensitivity and playing with a virtuosity that made him an unstoppable force.

The lesson: Feel empowered to combine seemingly unlike things to create something new and unexplored.

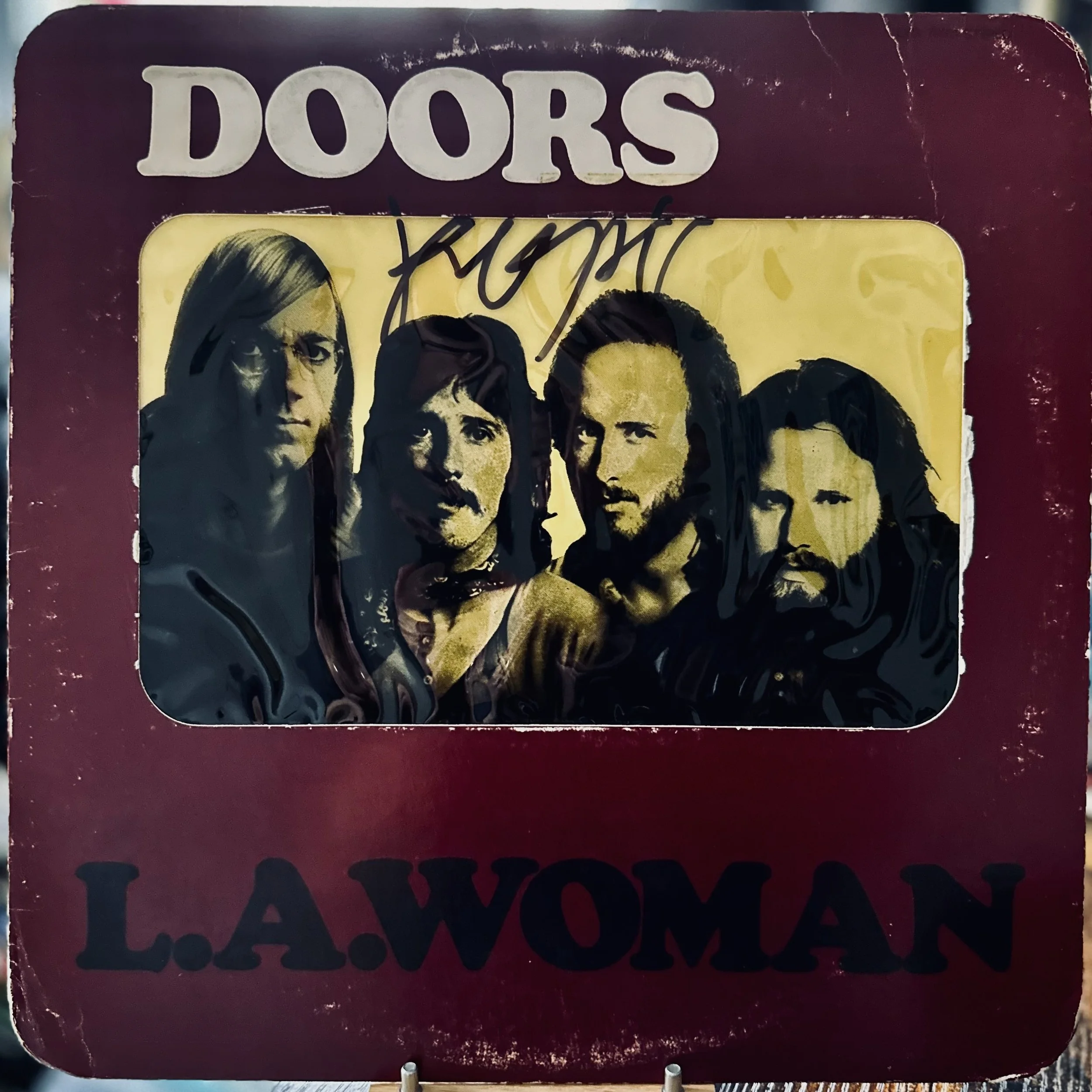

23. The Doors

There is a plethora of bands during the sixties and seventies who could easily belong on this list, but due to my self-imposed constraint, I could only include a handful. The Doors belong on this list not only in celebration of their music, but what they accomplished through their music for the genre. As with most acid rock bands, they were grounded firmly in a blues tradition, and the members were extraordinarily talented players. They are mostly remembered for the bombastic personality of Jim Morrison, but bear in mind that the musicality of the other members drove him to success. They successfully incorporated blues, jazz, country, funk, and classical influences in their songs, and they defied the three-minute pop/rock single format to help propel rock music as more than just a commodity.

Another factor is that they were the descendants of the Beat Generation. Morrison’s primary talent was his ability to write and perform what can best be described as beat poetry with an incredible band laying down the foundation behind him. Listen, for instance, to “When The Music’s Over” or “The End” and how the extended spoken word middle sections are made even more powerful by the interplay of the words with the band. Additionally, extended solo sections in songs like “Light My Fire” and “Riders on the Storm” have modal jazz-infused improvisation that drives some virtuosic guitar and keyboard work worthy of any jazz record. Even their weakest record by most critical standards, “The Soft Parade,” while admittedly a mixed bag and a low period for the band, has some underrated deep cuts in spite of the horns and strings added to make the band sound more commercially appealing. While Beat Poetry by the 1960s was somewhat out of fashion given the emergence of rock music as the most commodified art form for counterculture expression, Morrison’s bold choice to use the language of Beat Poetry was quite remarkable for its time, and ultimately served as a prototype for punk musicians, particularly Iggy Pop, who would employ the technique while incorporating provocative language directed at the audience.

One of the highlights of my life was seeing Robby Krieger, the guitarist, perform at the Whiskey-A-Go-Go club in LA, a spot frequented by the band in the sixties. I was even luck enough to pass Robby my copy of LA Woman for him to sign from the stage (pictured above).

The lesson: Find inspiration in the past and update it to make it your own.

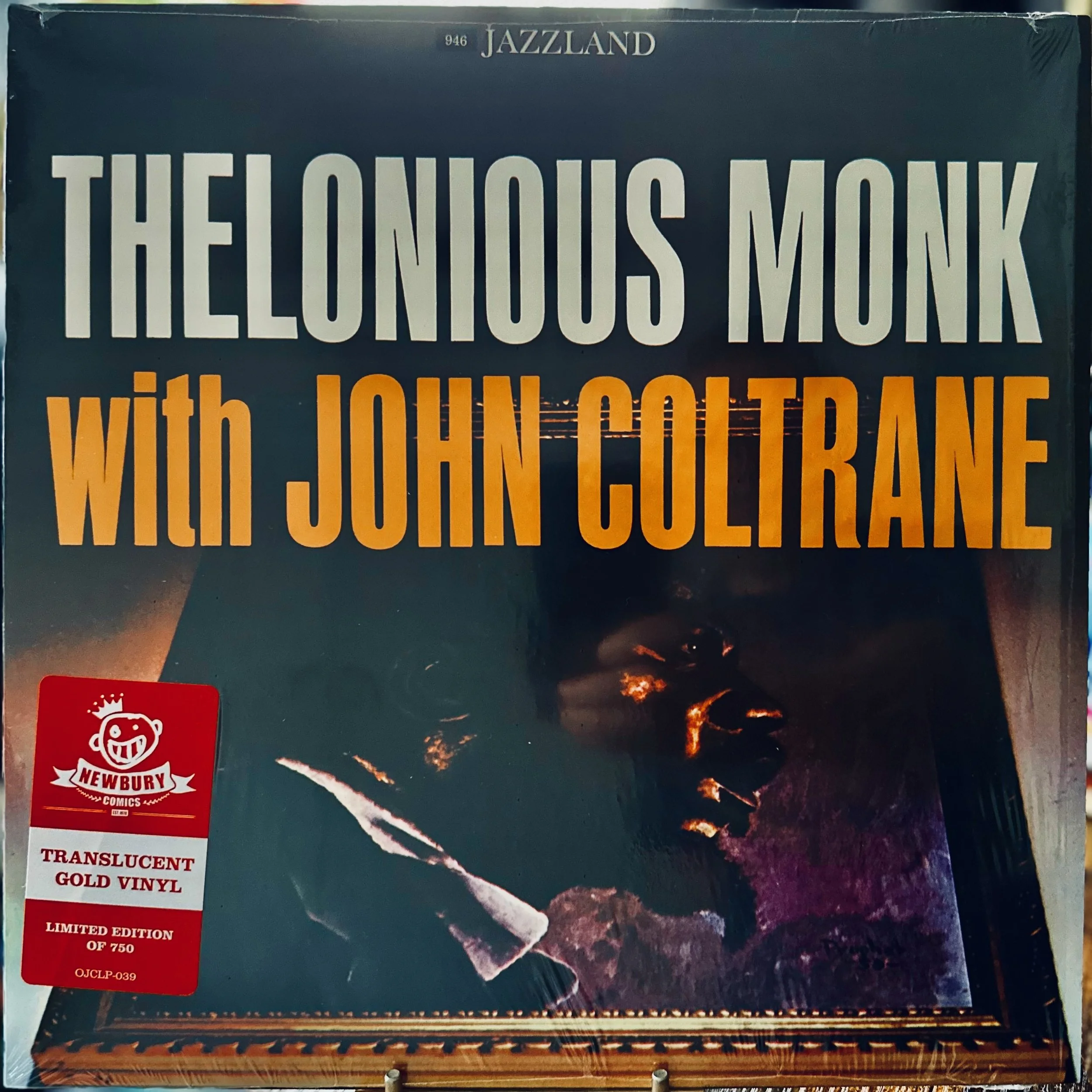

22. Thelonious Monk

One of the most eccentric personalities to emerge in the golden age of jazz was pianist Thelonious Monk. His songs, melodies, and improvisations employed strange rhythm patterns and chord clusters, often purposefully playing passages that sound “wrong.” Sometimes, his solos would be so minimalistic and off-putting that critics accused him of not being able to play piano, although this was far from the truth.

As like many creative geniuses, Monk just saw things differently. By exaggerating certain chords or notes on the off-beat or in a delayed manner, he forces his co-players to have to be at attention at all times - they never really knew what to expect from him, so they had to be prepared for anything. His melodies were often “tongue-twisters” that challenged even the most gifted of musician, although he was capable of quite beautiful melodies and arrangements. His mentorship of John Coltrane in the late 1950’s proved to be one of the most fruitful learning experiences of Trane’s life and helped propelled him to jazz immortality. One of Monk’s songs, “Ugly Beauty,” sums up his work perfectly.

The lesson: Ugly beauty is still beautiful if you know how to approach it.

21. Nine Inch Nails

If there is any person who can be considered the modern-day equivalent of Mozart, it would be Trent Reznor. The music that has poured out of this guy in the last quarter century is astonishing. I think of Mozart because of the way in which the rhythmic foundation of repeating patterns and the way it interacts with melodies and countermelodies to create a perfect harmonic structure is uncanny. Obviously, NIN is nothing like Mozartian chamber or orchestral music, but I think there is a degree of similarity with the way those two minds work.

The “Industrial” genre is not particularly easy to listen to, but it is quite rewarding if you give it a chance. It is essentially electronic music with a heavy metal edge, punk attitude, and strange machine-link sounds. Reznor is a master of this genre, and has extended its range into classical and jazz idioms. He has become a talented soundtrack composer and sought-out producer, as well.

His primary strength, in addition to his compositional prowess, are his lyrical subjects, in which he explores such dark lenses of the human soul that one wonders how he has survived this long. He documented his struggle with heroin, failures with loving relationships, and other misguided facets of his personality. Combined with the inventive and dark nature of his music, NIN is a force to be reckoned with. I would encourage you to listen to them from a music lens and try to get past the aggressive and hostile nature of the lyrics to appreciate the value of his artistic achievements. And let his lyrics serve as a lesson to you about the temptation of exploring the dark side of human nature firsthand.

The lesson: Don’t do heroin.

20. Pablo Casals

I have been listening to the Bach Cello Suites played by Pablo Casals from before I can remember. Your grandfather used to play the recordings quite a lot. In third grade, when it was time for me to choose which string instrument I wanted to play in school, I chose the cello because of my love of the sounds and atmosphere evoked in those recordings. When I listen, to this day, I can smell the air of the past, and am transported back to another world, one of my imagination, a world that never was, but one that is real, all the same.

The interesting thing about Casals is that he was not the most technically gifted cellist. Many have come after him whose virtuosity far surpassed his. However, he was the first cellist whose recordings became internationally known when the recording industry was in its infancy. It is fortunate because the poor sound quality of his recordings adds to the timelessness and mystery of the sound he generated. He was also the first to re-discover the Bach Cello Suites, and afterward, they became standard repertoire.

His other recordings are numerous, but his signature is forever written upon the Cello Suites. I remember every note of them and tried to model my own cello playing after him in later years. He did not seek out perfection or precision in his style, but this made his recordings all the more human and attainable. Sure, it is wonderful to listen to the cello performed as flawlessly as Yo-Yo Ma or expressively as Jacqueline du Pre, but with Casals, there was a level of authenticity embedded within the sound which has forever left an impression upon me.

The lesson: Seek authenticity, not perfection, in all that you do.

19. The Rolling Stones

The Stones are one of the greatest rock bands ever. It is impressive that a band that started playing sixty years ago is still around. They came out around the same time as the Beatles, and were often viewed as the anti-Beatles, creating a bad-boy image that ran contrary to the Beatles’ clean and ready-to-please personas. Unlike the Beatles, their passion was more in American blues than rock and roll, and their music was more reflective of idiom than their contemporaries. They also pioneered a format - a group fronted by a lead singer rather than a lead singer backed by a group - which had a lasting impact on the way rock groups evolved.

Their contribution, however, extends beyond their role in developing rock music. After the psychedelic height of acid rock in 1967, which wasn’t in the Stones’ wheelhouse, they put out a set of albums that are flawless: Beggar’s Banquet (1968), Let It Bleed (1969), Stick Fingers (1970), and the double-album Exile on Main Street (1972). The rest of their music after this period tended toward mediocrity with moments of brilliance rather than the raw perfection of these four records, but their contribution to rock cannot be understated.

The lesson: Don't be afraid to be bad once in a while and break some rules - it can be fun.

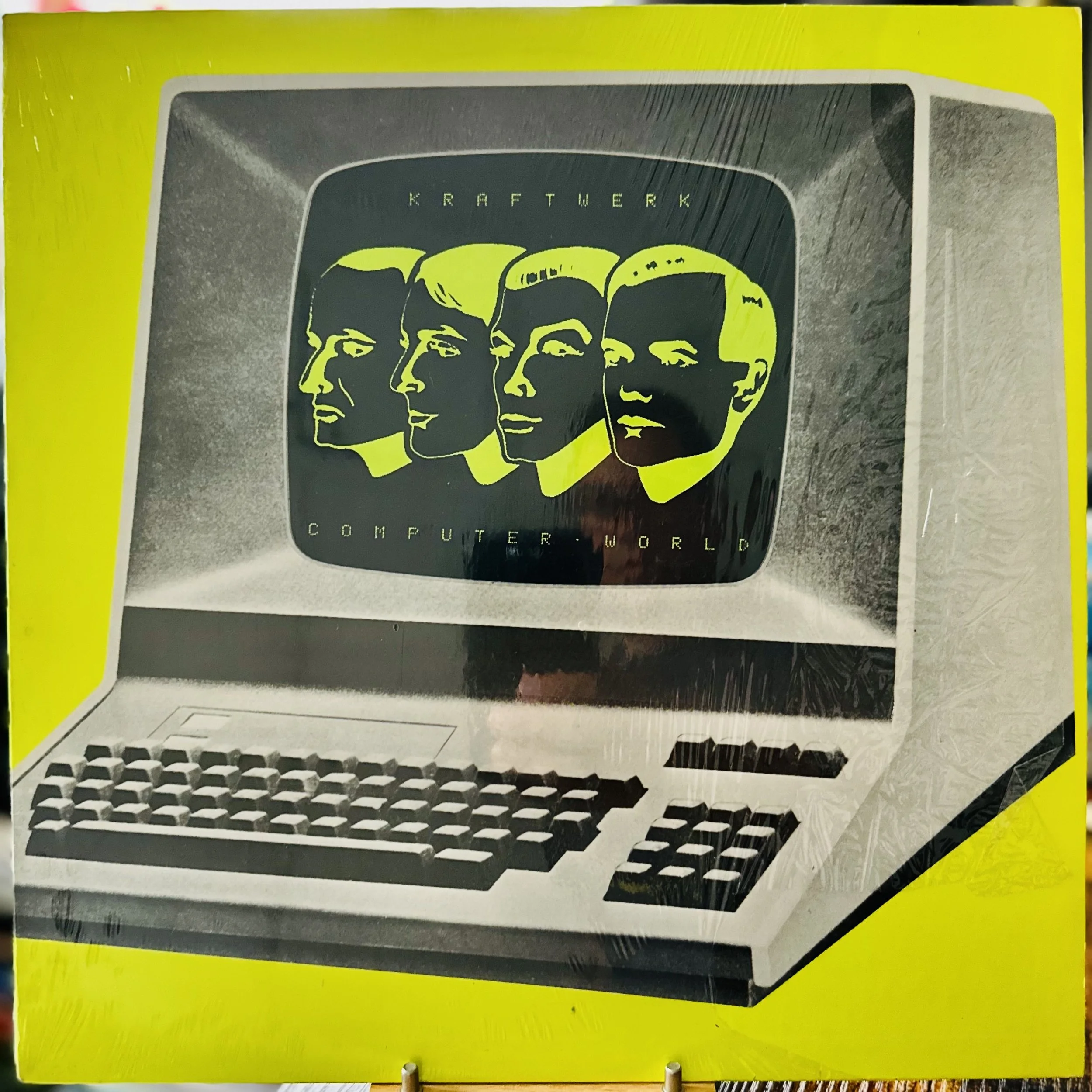

18. Kraftwerk

I love the music of Kraftwerk. When I first heard it, it was quite literally unlike anything else I had ever heard. It is electronic, yet organic. It is rigid, yet danceable. It is serious, and yet fun. Kraftwerk were pioneers of electronic music, but what they accomplished was far more remarkable.

The act of composition is a complex craft. In the same way that a painter begins with a blank canvas or the way that a writer begins with a blank sheet of paper and has to create something out of nothing, a composer begins with silence. The task is to organize sound into music, and this is traditionally done with instruments and/or voices and organized into a given structure with such elements as rhythm, melody, harmony, etc. However, there is no rule that says music must be made with instruments. As technology develops, it enables people to make new kinds of sounds. Instruments, after all, are a type of technology that exist only because someone invented them. Cavemen, after all, could not sit down and strum a guitar because it had not yet been invented, but that does not mean they were incapable of creating music.

Kraftwerk used electronic instruments and computers to create their music. They are not the first, nor will they be the last, to do so, but in my opinion, they were the best. What stands out to me is the manner in which they used technology as a compositional tool. In other words, their music could not be made without the technology used to perform it. The technology informs the compositional process and enables the performers to explore ideas in a way they wouldn’t otherwise be able to do. They were masterful at this, and their catalog demonstrates it.

The lesson: Don’t be afraid to try something new, and don’t let other people dictate what you can and can’t do.

17. Clifford Brown

Brownie was a jazz trumpeter who I came to love and admire through my uncle. My uncle, a trumpet player himself, worshiped him. I think that, as opposed to a figure like Miles Davis, who was somewhat limited in ability but gifted in composition and exploring different musical styles, Clifford Brown limited his playing to just one style (hard bop) but was one of the most extraordinary players in the world.

His story as a jazzman of the 1950s is somewhat unusual. During an era when alcohol and marijuana were expected and heroin was typical, he did not drink or take drugs. He had a family whom he loved and valued, and was known to be humble and focused. Tragically, he died in a car crash at the age of 25 along with pianist Richie Powell. Given that he played professionally for less than a decade, his output is remarkable. His records, especially those made with co-leader and drummer Max Roach, are the absolute pinnacle of what hard-bop jazz ever reached. The album Study in Brown is in my top five favorite jazz records. One can only imagine what he would have achieved had he lived longer, but I am just grateful that he had the time he had.

The Lesson: Life is short, so make the most of it.

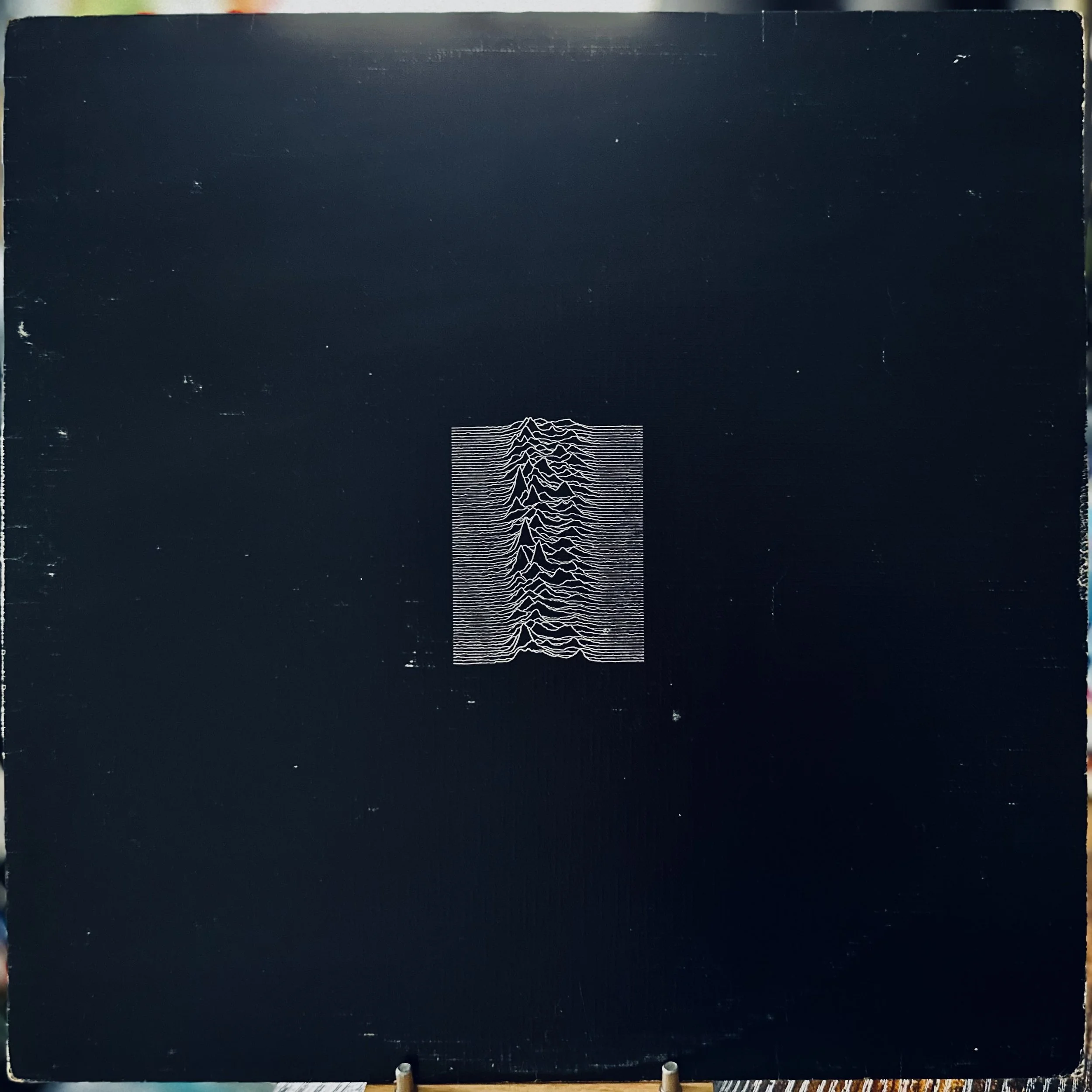

16. Joy Division / New Order

Listening to Unknown Pleasures (1979) for the first time was a revelation. In it, I heard the dark poetic beauty of Ian Curtis, the complex and almost machine-like drumming of Stephen Morris, Peter Hook’s bass played like a lead guitar, and the understated but innovated guitar lines of Bernard Sumner, who's playing sounded, at times, like a complex polyphonic counterpoint against the bass line. It taught me where the notion of “post-punk” came from, and what it meant. I understood how this branch of rock music was unlike any other, and how it deconstructed and reconstructed punk into something new, eerily dreary but just as angry, and with a dark, gothic quality never achieved by the Ramones or the Sex Pistols. I understood where bands like the Cure, Bauhaus, Depeche Mode, and others got their inspiration.

If hearing this album was a revelation, then hearing their second album, Closer (1980), was even more powerful because I understood how they stretched their music into even further depths, especially by adding the synthesizer. I listened to these two albums non-stop and studied their sounds and words, but when I found out that follow Ian Curtis’ suicide, the band re-grouped with a new member under the name New Order, and that this band still plays to this day, I was enthralled. The music of New Order is the realization of all that Joy Division promised its listeners in a fun and danceable way. Electronica? Techno? Pop? Rock? I don’t know how to describe it but it had all the qualities of Joy Division I loved with a more commercial sound. These bands forced me to transition my attention from the classic rock of the sixties and seventies to the post-punk and new wave bands of the eighties, which revealed to me a whole new music language I never knew existed.

The lesson: There can be beauty, and even fun, in darkness. Don’t shut yourself off to it.

15. Talking Heads

Talking Heads are a band that shifted my perspective of music. They emerged from the New York CBGB scene in the mid-seventies, and as they gained popularity their music became increasingly inventive. Their diverse range of influences was reflected in their unique music and strange lyrics, as well as their impressive visual component documented in the film Stop Making Sense. There is truly no other band quite like them.

Their creative process is interesting; while it is true that the band was largely dominated by leader David Byrne, who generally supplied all the lyrics and fronted the band, the music is the result of a collaborative process between the musicians. On some records, they focused less on actual songs and more on creative different grooves and patterns that they would explore and develop. Eventually, Byrne would supply his signature eccentrically brilliant words, and their magic was generated. I am fascinated by the idea that a band can work together to create a unique blend of sounds, and use that as a canvas for creating a song, as opposed to simply writing, arranging, and recording one. It is more like constructing a song out of lego blocks rather than writing it from scratch.

The band was not the first to do this, and it isn’t even how they made all their albums, but it certainly was how they made their best ones. Radiohead is another band that later emulated this process, as was Fugazi, but the diverse range of styles and influences combined with the inventive lyrics, make Talking Heads stand out as the true masters in the field.

The lesson: Learn to collaborate with others, no matter what you are doing. Generally, the whole is made stronger by its components, so whatever your role is, do it to the best of your ability and contribute.

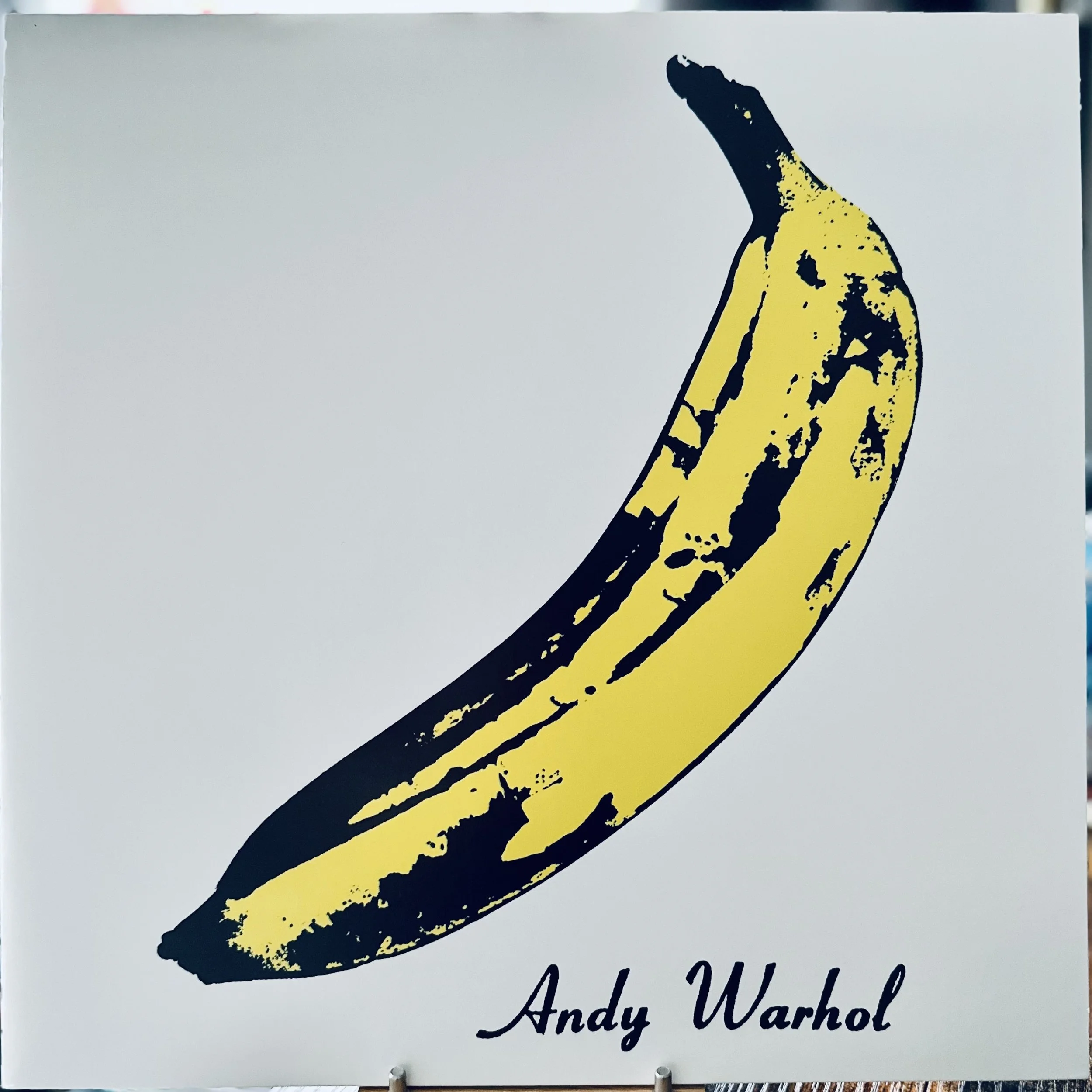

14. The Velvet Underground / Lou Reed

There was a moment in music in which the so-called hippies began to diverge into various sub-genres. Let’s use this relatively arbitrary example: three bands who, in the mid-sixties, typically played with psychedelic projections in the background and were, to some degree, associated with the underground music and art scene were Pink Floyd (London), The Grateful Dead (San Francisco), and The Velvet Underground (New York). Pink Floyd eventually explored more ambient, conceptual music which came to be known as “progressive rock.” The Dead explored loose, American styles like blues, country, and jazz to create long-form extended improvisations and became known as a “jam band.” The Velvet Underground, who had ties to Andy Warhol and were the heirs apparent to the Beat Generation, went in an entirely different direction.

While it is easy to point to a single band or even record as being the “origin” of a genre, it is often somewhat arbitrary and over-generalized to do so; having said that, if there is a single point of origin of the music that came to be known as “punk,” I would consider it to be The Velvet Underground.

Punk music, as a genre, is difficult to define because the music that falls under its umbrella is widely varied. The Ramones played fast, loud, and short songs that explored seemingly inappropriate topics and were sung aggressively. The Sex Pistols and The Clash in the UK, while similar in their aggressive nature, were slightly less formulaic and the music was more angular and syncopated than The Ramone’s chompy power chords. There were “glam” acts like the New York Dolls who reversed gender stereotypes, “garage” bands like The Stooges, revolutionary bands like the MC5, and hardcore groups like Minor Threat and Dead Kennedys who stripped down their music to the bare essentials and often did away with melody and form altogether.

The Velvet Underground did none of those things. Their early music can even be characterized as “psychedelic” to an extent. However, they embodied that notion of the “other,” which in my perspective is central to the philosophy of punk. Just as the Beats before them, they engaged in the counterculture and documented it with their lyrics. They explored topics like sexuality, homosexuality, drug use, and sadomasochism to an explicit and direct degree that had not been done before. True, listeners all knew what The Doors meant by “Light My Fire” or what The Stones wanted to do when they mentioned a “needle and a spoon,” but the innuendo was stripped away by the Velvets. There is little room for interpretation in a song called “Heroin.”

Musically, there was no other band who sounded like them. The music was decidedly uncommercial, messy, and down-right weird. It was artsy without being pretentious, and aggressive without being combative. More importantly, they romanticized the role of the other, the person who does not have a place in society with character sketches of drug addicts and perverts, or people who did not find any place in mainstream society. Given Lou Reed’s background as a bisexual man who was forced into undergoing shock therapy, it is not surprising that he adopted this approach. It is a key premise to punk: I don’t want to be in your club, so I will make my own and I don’t want you in mine.

The normalization of a counterculture is natural; as popular trends develop, there will always be reactions against them, and new genres or methods of expression are born. Punks, like the Beats, were the realization of this phenomenon; but the idea that you are part of a society outside of society, a culture that thrives on the destruction or normalized culture - this was new. The Velvets did not just approach their music with the “let’s make this counterculture genre popular” approach; the differentiating factor was “I don’t care what you or anybody think of this music.” Of course, this approach did not last forever. It is not an entirely sustainable business model, so to speak, but it did create a ripple that resonated deeply with people and eventually came to fruition in a flurry of sub-genres of punk and countless bands and artists who felt it.

The Lesson: “I don’t care what you or anybody else thinks” is a powerful lens of self-affirmation and empowers you to be true to yourself. Be a punk.

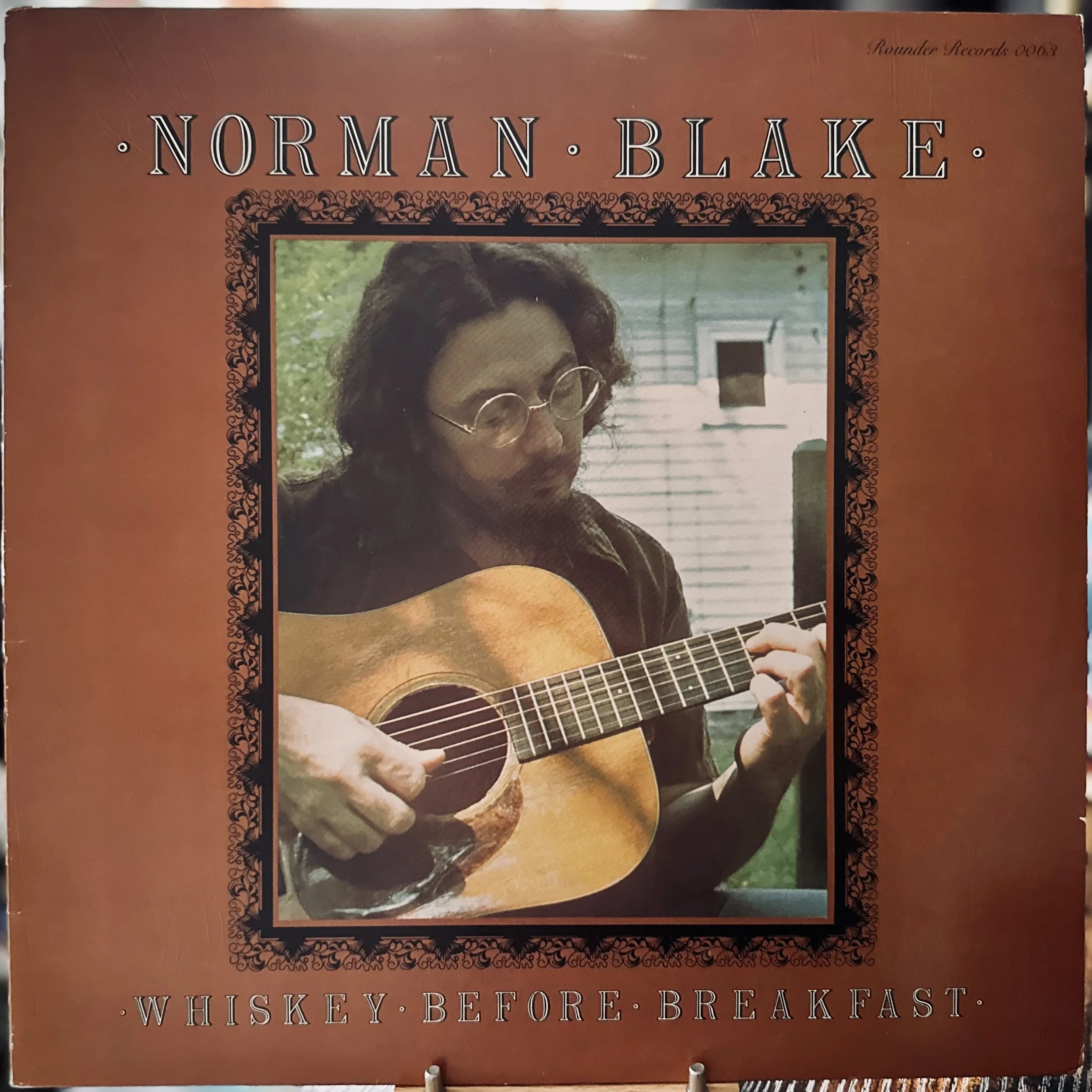

13. Norman Blake

I was very close to your great uncle Rick growing up. He was a music teacher and introduced me to many musical artists. One such musician was the great Bluegrass guitarist and multi-instrumentalist Norman Blake. He was a part of the New Grass movement of the seventies which sought to develop and evolve the language of Bluegrass while still preserving its roots and values.

Blake was a profoundly talented session musician; he was famously featured on Bob Dylan’s Nashville Skyline, and backed up Johnny Cash. He began to release records in the mid-seventies featuring both traditional and original songs. He could play runs faster than anybody, but his style was still subtle and refined. He did not show off or deviate too far from the melody but rather kept his solos closely related to the melody while creating variations and ideas around it. His rhythmic styling perfectly captures the chord changes while featuring a prominent bass line. His songs could be funny or heart-breaking, but always managed to paint a picture of the mythical Gothic South as vividly as Faulkner’s writing.

Blake also played other instruments, including the mandolin and fiddle. He transformed simple melodies into head-spinningly complex music statements with an elegance that few ever possess. My favorite record is called Whisky Before Breakfast (1976) which features the song “Church Street Blues.” This was the song my uncle and I obsessed over. We used to drive from Connecticut to Nazareth, PA to the Martin Guitar Factory. Blake favored Martin Guitars, and for us, this annual pilgrimage was a way of preserving our love and admiration for the craft of guitar making and playing.

Blake was (and still is) a purist. He sings about the Civil War, steam trains, and hobos. He has the soul of Woody Gutherie and John Steinbeck but plays with the passion and imagination of Jimi Hendrix. But, as I said, he did not show off. His solos were pure beauty, not fireworks. And this constraint suits his music perfectly.

The lesson: Just because you can, doesn’t mean you should; there can be beauty in constraint.

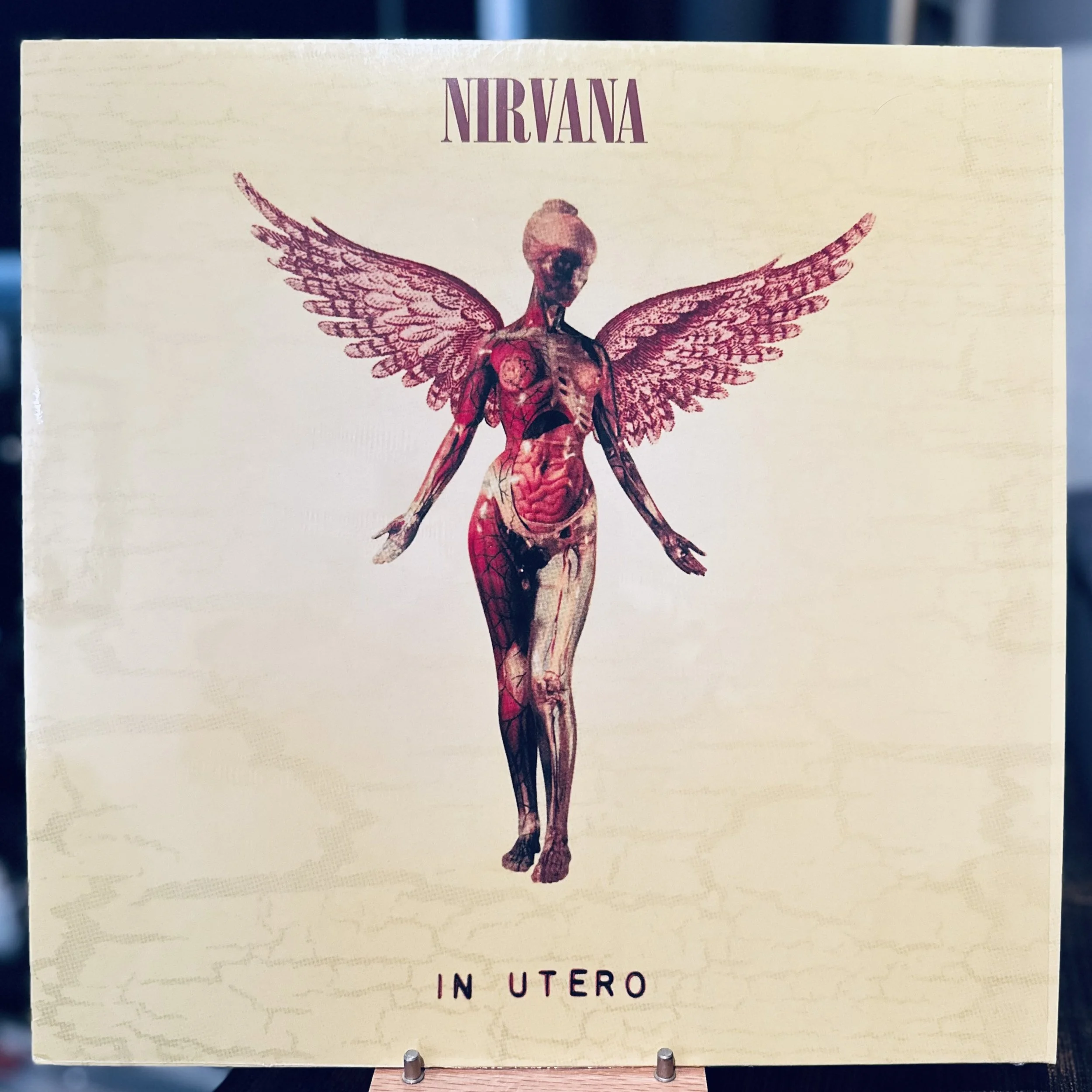

12. Nirvana

I remember the day I learned that Kurt Cobain died. I was nine, and your Aunt Sarah, who was a huge Nirvana fan, was 14. Although I always denied liking “her music” (grunge/alternative rock), I secretly loved it. It made me feel older, wiser, cooler, and “in the know.” It seemed like Nirvana set the bar and everyone else copied them. Of course, that wasn’t truly the case, but the popularity of their album Nevermind (1991) widened the threshold of acceptance of alternative rock. What was previously considered too hard for mainstream audiences became mainstream, and alternative music blossomed until the point that it fully assimilated and became part of the norm. Rock music in the nineties was changed by Nirvana, and has never been the same since.

I wept that day. Not cried, but wept. I knew even then that it was the end of an era. We lost our spokesman, our leader, the man who called out cultural hypocrisy and represented the sarcastic dismissal of boomer values. I was not alive when Lennon was shot, but Cobain’s death was our version of it. He became a member of the infamous 27 club, along with Hendrix, Joplin, Morrison, Pigpen, and Brian Jones. Unlike those musicians, he did not die of an overdose or accidental causes. He shot himself. He did it to himself. Did that mean that all he stood for was false, just an illusion or a marketing ploy? Did the boomers really win?

No - we cannot assign such value to a single man. He was a guitarist and singer, a brilliant one who appeared in the right place at the right time and got the credit for his genius that he rightly deserved. The rest were forces largely beyond his control, and driven more by commercial interests than cultural philosophy, and he was put under more pressure than he could endure. It broke him, and he is ultimately a tragic figure. Having said that, the music he left behind resonates to this day, and does not sound dated or stylish. It stands the test of time because of its quality. When I think about Nirvana these days, I think less about the cultural icon Kurt Cobain and more about one of the best bands in the world who created music that rocks my socks off.

The lesson: Don’t turn people into idols. People are people. Respect what they do, love them for who they are, but if you idolize them, your bubble will eventually burst.

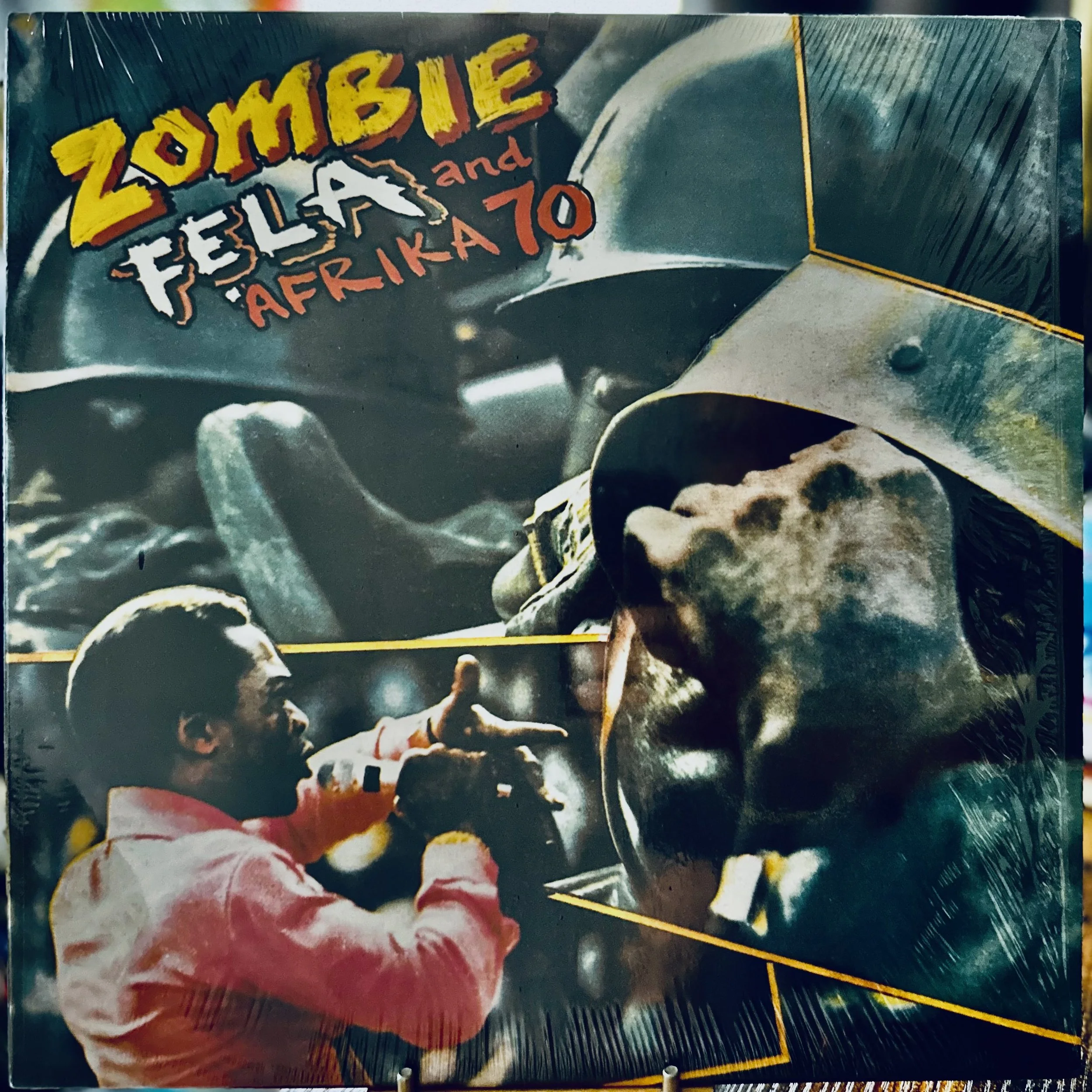

11. Fela Kuti

I cannot think of any musician who suffered more for the cause of human rights than Fela Kuti. Speaking out against the corrupt Nigerian government caused him to be wrongly jailed, physically assaulted, and bear witness to the murder of his mother and the destruction of his home. His efforts brought international light to the human rights violations taking place throughout Africa, and set the standard for the musician-as-political-activist archetype that was soon adopted by Bob Marley in Jamaica.

His music is extraordinary. Fusing American soul and funk with African rhythmic drive and his fiery lyrics, and defies expectations with every listening. The first time I heard it, I felt as though I had just seen a new color for the very first time. It opened my eyes to African music, and I could understand how groups like Talking Heads used his style as a template for creating their own. I cannot help but tap my foot and sing along during the call-and-response sections because the music is so naturally visceral that my body cannot ignore it. But his voice and message is clear and should serve as inspiration to anyone who speaks out against bullies.

The lesson: Speak out against injustice loud enough that people will hear.

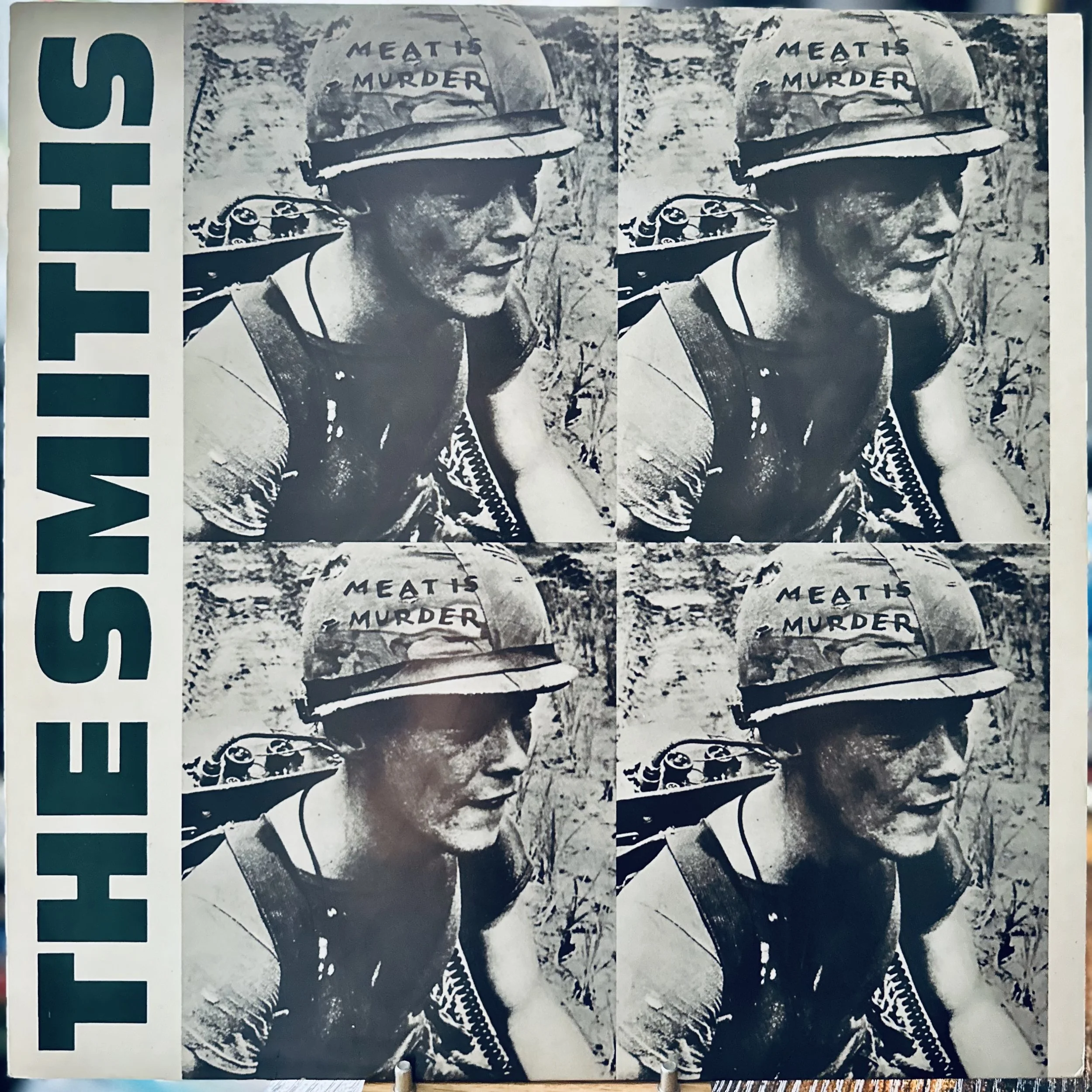

10. The Smiths

The Smiths’ lyricism is poetic, dark, and brilliant. It expresses a sadness that is so personal, yet so relatable while masking it with a catchy pop veneer. The guitar playing of Johnny Marr is incredible; I believe he is the single most underrated guitarist of the eighties. He didn’t grandstand or use distorted, fast licks like many of his contemporaries, yet his sound was clean and complex. The way he moves between chords with constant passing tones, arpeggios, and circular riffs - motion, motion, motion. The genius of the Smiths is that the sense of anxiety comes not only from the words but also from the guitar passages.

Their song structures are also very interesting. Morrissey often doesn’t structure his words to follow an obvious schema, but lines just come with no apparent rhyme or relationship to those before or after. Sometimes they repeat, and sometimes they come after long spans of silence. The generic form of verse/chorus/verse doesn’t appear to capture his train of thought or mode of expression.

I sense an unspoken but ever-present theme of existentialism in his words. Things come and go, life happens to us. “We are born, and then we live, and then we die.” I think this point of view enables Morrissey to construct his own morality. After all, if there is no higher power or predetermined purpose, why can we not assign value or meaning to whatever we want? “Meat is murder” because he says it is, which may be that is ultimately more moral than blindly following a figurehead (the Queen) or a doctrine (the Church). This perspective had a profound impact on my thinking.

There was a point at which your mother could no longer listen to their music because I played it too often. Fair enough, but you know what - I don’t think a person can listen to The Queen is Dead or Meat is Murder enough in a lifetime, and I got off to a late start. When I bought my first Smiths record, the single “What Difference Does It Make,” it was not what I expected. I kept hearing about them and didn't know what I expected, but I was surprised by what I got. But I liked it and kept on getting their records. The great thing is, my interest kept branching out. I began moving past the Classic Rock era of my youth, the stuff I knew and grew up on, and began to discover the New Wave renaissance of the seventies and eighties. Talking Heads. Patti Smith. Elvis Costello. Joy Division. New Order. The Cure. Television. David Bowie. In that sense, their music opened my mind to many new perspectives and my ears to a plethora of brilliant artists.

Lesson: The story of the underdog can be more impressive than that of the hero. Try to tell both stories.

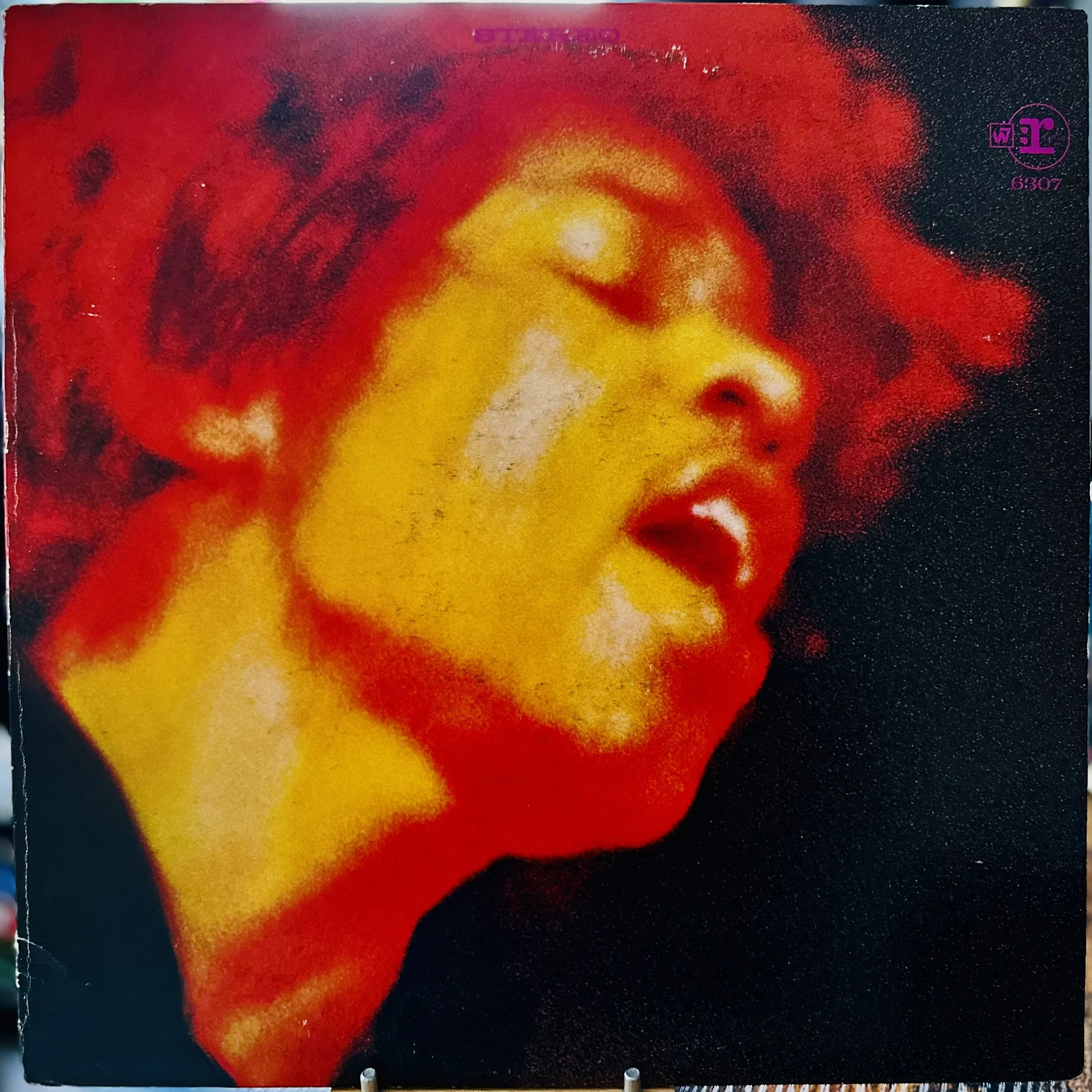

9. Jimi Hendrix

When I first watched the movie Woodstock I must have been about 11 or 12, and it changed my entire perspective of the world. I had been obsessed with the Beatles up to that point, listening to and studying them endlessly. I had a similar interest in Dylan and The Rolling Stones, but Woodstock turned me on to many of the other bands of the era, especially those who peaked around this time. Janis Joplin. The Who. Jefferson Airplane. CSN&Y. Santana. But the guy who really blew me away was Jimi Hendrix. Seeing his performance, especially the climactic “Star Spangled Banner,” blew my mind. I didn’t know that a guitar could sound like that - but even more importantly, I wondered why the hell every guitar didn’t sound like that. The way he gripped his guitar, the way his fingers wrapped around it, it was unreal. He appeared to be moving in fast motion.

Naturally, I started collecting his music like it was the air I needed to breathe. His albums, his live recordings, his compilations. For a dude that only was around professionally for less than four years, his output is astonishing. I even bought my first guitar - a white Fender Stratocaster modeled after the one he played at Woodstock, complete with an upside-down headstock (to simulate the way he as a lefthander played an upside-down guitar) and an engraving of the man himself on the back plate.

Hendrix, in my mind, completed what I came to see as the Holy Trinity: The Beatles, Dylan, and Hendrix. Dylan was the Father - the voice of truth and reason. Hendrix was the Son - the rock savior with his guitar that could evoke the wrath of God. The Beatles were the Holy Spirit - the source of it all, the origins of the religion of rock. This was my religion, and from these three figures, I learned about the rest of the first golden age of rock and roll. The Doors. The Dead. Zeppelin. Cream. Floyd. You get the point - the music of the sixties and seventies. But, as far as Hendrix was concerned, I was thunderstruck and have never looked back. I have made every attempt to collect every note the man committed to tape in order to keep his Gospel alive.

I do realize, of course, how silly this sounds. He was, after all, just a guitarist, not a religious figure. But he did believe that his music was a religion, of sorts, maybe the religion that we need in the absence of real religion. It is a spiritual experience. Is it that farfetched to consider that in playing his music, Hendrix was touched by the hand of God any less than Brahms or Beethoven? He called it the Electric Church, and I still attend regularly.

The lesson: Spirituality is anything that touches your soul. Listen to it, follow it, and stay true to it. It can come from anywhere, and don’t let anyone tell you differently.

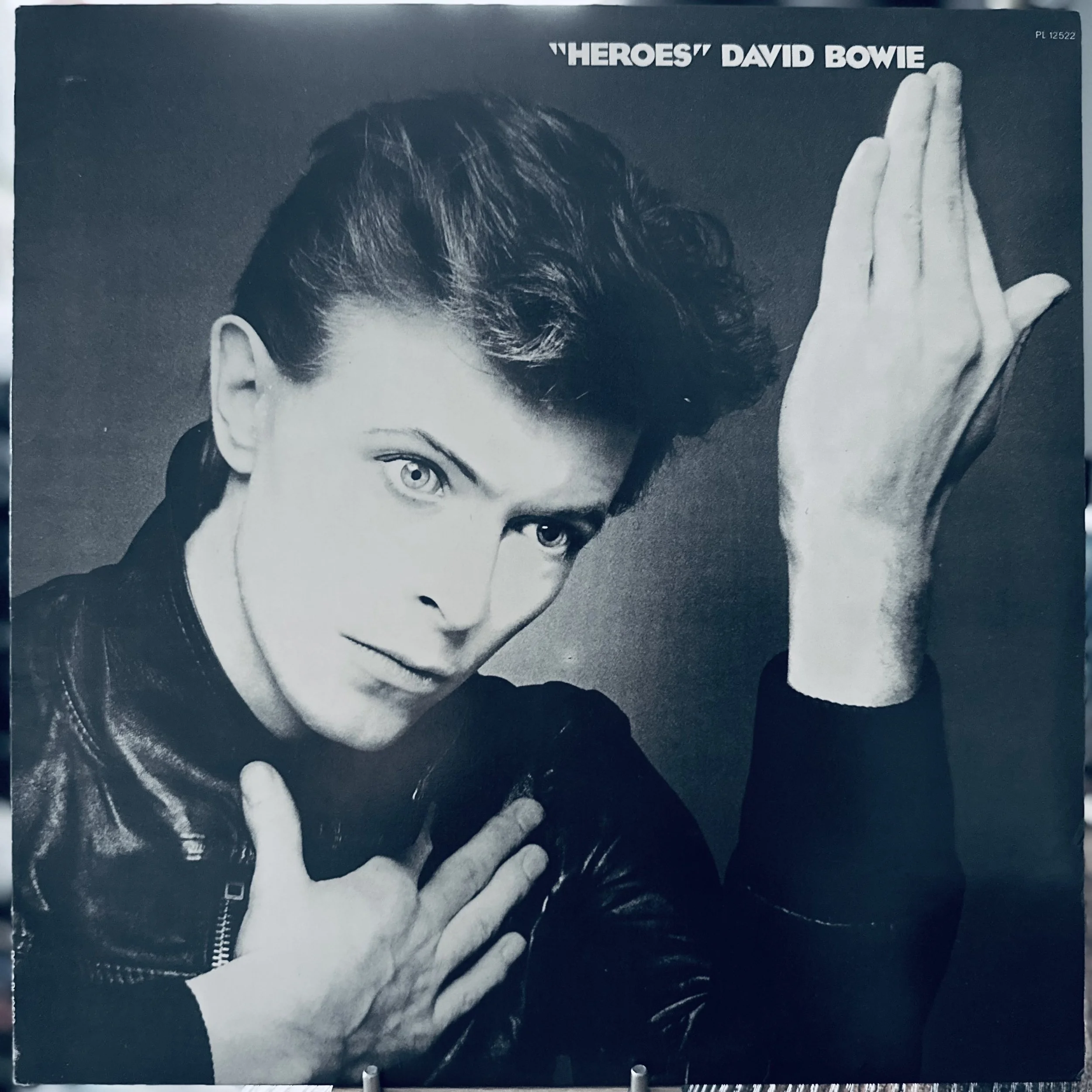

8. David Bowie

As an adult, a friend once told me that I should give David Bowie a chance. I was either not interested in his music or had passively dismissed him as a cheesy pop star. I think I might have seen the video he did with Mick Jagger for “Dancing in the Streets” and subsequently written him off. But the recommendation, along with my growing awareness of his reputation as an artistic and musical force to be reckoned with, was enough to give me the push I needed.

I am sorry to say that the first “album” I got was his greatest hits. I suppose, in retrospect, it was better this way, as it gave me an easy path in, an opportunity to sample his most popular moments and offer a bird’s eye view of the development of his career. This set glossed over his Berlin Trilogy, now my favorite era, so it was not a particularly insightful collection, but it might have been too soon for me to experience that stuff, anyway.

I did, however, like what I heard. I found I knew a lot of the songs anyway, even if I didn’t know they were his, and after this, I moved on to my first album, Ziggy Stardust (1972). One by one, I got the albums and I dug deeper and deeper. I began to understand his career trajectory, his application of fashion and visual aesthetics, his androgyny and ambiguous sexuality, and his voice. His art was a multi-factored experience, appealing to more senses than just the one focused on listening. Musically, there was substance, but there was a Warholian pop-art aesthetic, as well.

I think the album that really took me the most by surprise was Station to Station. That opening track - Jesus! The funk of “Stay” and “Golden Years.” The vocal performance on “Wild is the Wind.” After digging into this album, I decided to dive deep into his subsequent Berlin Trilogy. I remember hearing Low for the first time and not knowing what to think or feel. This was a guy I had come to idolize, and I hadn’t even heard his best album.

Then, he died. At the beginning of 2016, he gave us an album. A masterpiece, his masterpiece. Blackstar. Two days later, he was gone. Whatever self-mythologizing he was responsible for throughout his career, this sealed the deal - it was the ultimate masterstroke. Legend became a myth, and the myth became a god. I continue to listen, appreciate, and learn, although my obsession has waned a bit. So while I cannot say I “grew up” on David Bowie, the way that I “grew up” on Dylan or the Beatles, I think, in a way, I did grow up a bit as a result of his music. It was part of that era of musical discovery for me that ran in parallel with the Smiths. Kraftwerk and Talking Heads suddenly made sense to me, and the connections to Lou Reed & Iggy Pop piqued my interest, as well. The music of my adulthood shed new light on the music of my childhood. As his music and art become more deeply ingrained in my conscience, the obsession wears down, but the awe and respect continue to grow.

Lesson: Figure out what quirk makes you you, and capitalize upon it. Your unique you-ness makes you the only you there is.

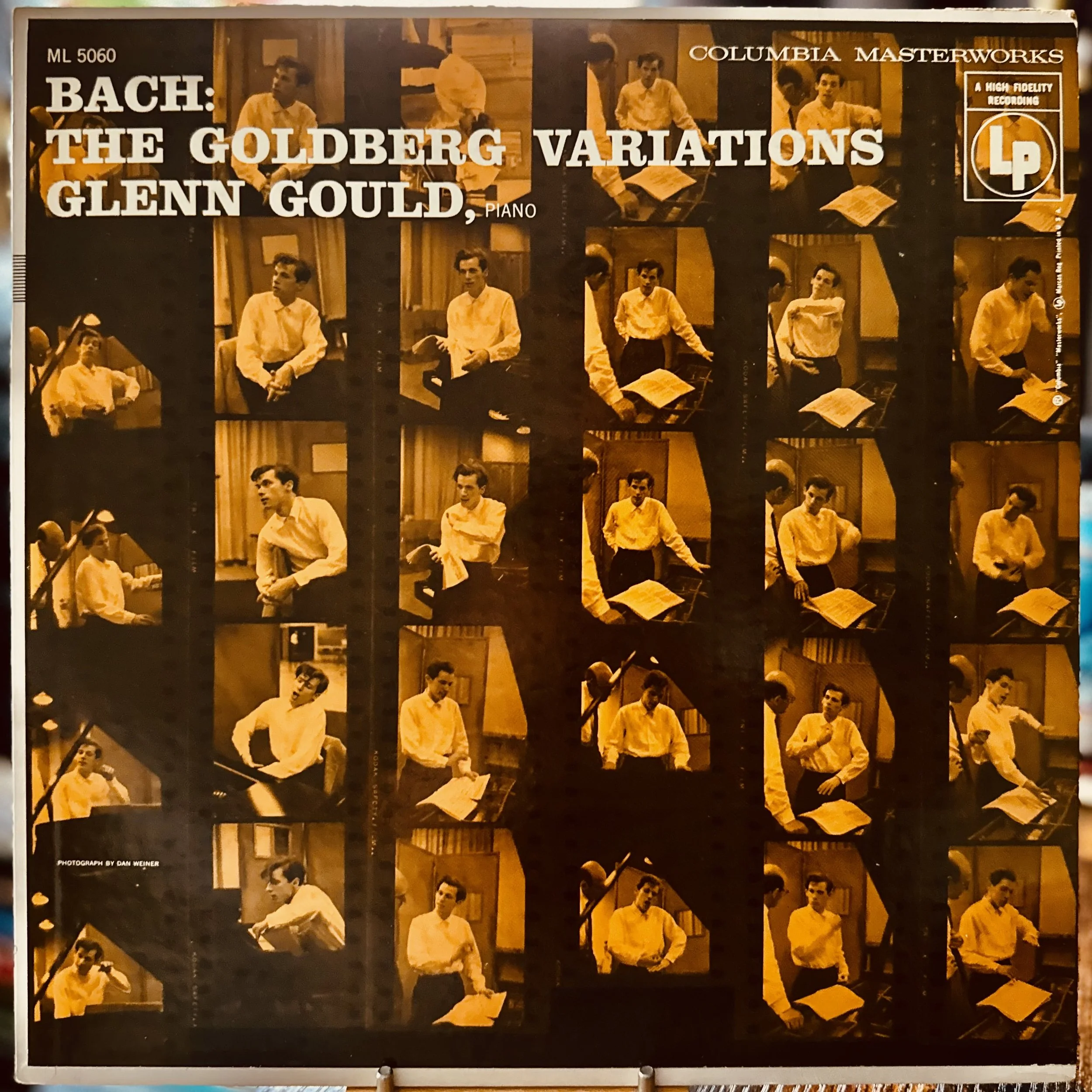

7. Glenn Gould

Although he is known primarily for his recordings of the keyboard works of Bach, Glenn Gould’s recorded output as a classical pianist is quite extensive. He was a genius, and incredibly eccentric. His most famous piece was the first recording he made, Bach’s Goldberg Variations (1956). This recording is extraordinary and solidified his place as a legendary pianist. He revived the popularity of the piece, and it catapulted his reputation as a key interpreter of Bach. He recorded almost all of Bach’s keyboard works and his recordings are considered the definitive versions by many listeners.

His style was unique - his attack of the keys, his lack of sustain pedal, and the melodies and countermelodies that he emphasized. His style was perfectly suited to the polyphonic language of Bach’s work, and Baroque music in particular. He was not, however, celebrated for his Romantic performances, such as Beethoven, Brahms, and Chopin - in fact he openly criticized those composers. He did, however, excel at 20th-century music, particularly Schoenberg, whose style, although atonal, was largely polyphonic in the way that Bach’s was. I gravitate to his recordings of Bach and 20th-century composers.

He famously stopped performing live and devoted himself exclusively to studio recording (just like the Beatles). He believed that performance was not an authentic experience, but rather, a battle between the audience and the performer. The audience sits in judgment, just waiting for the performer to make one mistake that they could focus upon. Although this perspective is exaggerated, there is a degree of truth in it. He believed that in the studio, through the use of tape editing, a performer can create a perfect musical interpretation. His recordings are a testament to this theory and are still regarded as such.

Your grandfather and great-uncle had a fascination with Gould, especially because Bach is their favorite composer. Because of this, I grew up listening to him quite a bit, and have adopted his perspective as to how “perfection” can be achieved through artificial means without losing any integrity or authenticity. His recordings are like magical pathways through dark corridors of the imagination, musty and old but mystical nonetheless.

His career was bookmarked by the Goldberg Variations. Toward the end of his life, he re-recorded the piece (1981). It is fun to compare and contrast the two recordings. The first is by a young and energetic prodigy who is not shy about demonstrating his skill. The second is by a wise, learned man who favors musical cohesiveness and rhythmic continuity over virtuosic exhibitionism. He believed that there is an underlying pulse that unifies the piece and saw the variations as separate pieces of a whole (as opposed to independent songs). It is beautiful because it really sums up the evolution that he underwent, both as a musician and as a human, and signifies the evolution that continues in the world of art music and how listeners react to it.

Lesson: Do not be afraid to be eccentric, as long as it is authentic to you. It might enable you to see the world in ways that others don’t.

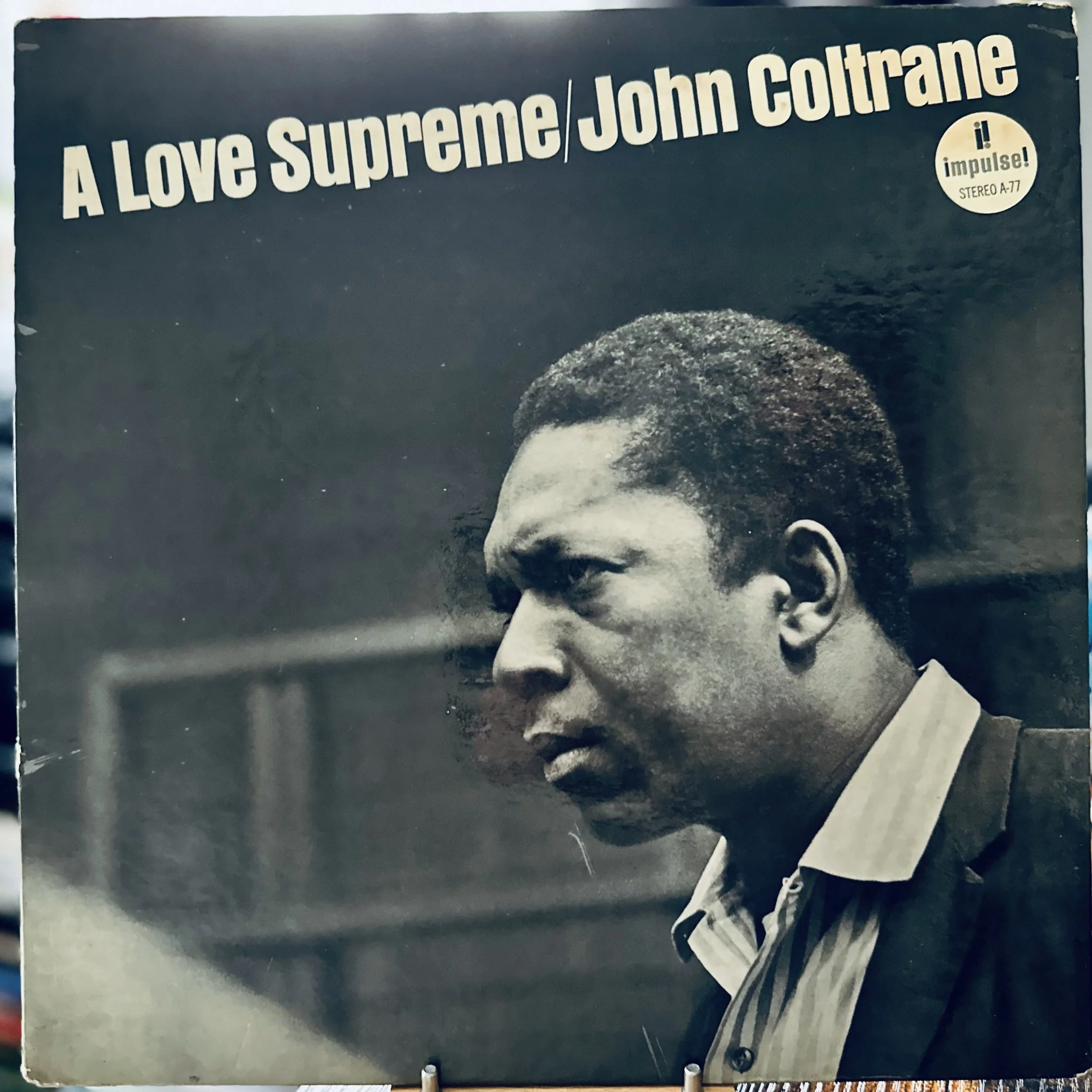

6. John Coltrane

Let me be clear - John Coltrane is the greatest jazz musician who ever lived. Ever.

He had the mind of an Einstein or Shakespeare, but for music. He saw the universe in a way that no one else could conceive of. He found ways of uncovering entire languages within a note by deconstructing and reconstructing it. He spoke the language of classical Indian music and made it swing. He pushed the boundaries of atonality, modality, unmetered rhythm, and form to degrees unexplored by most contemporary composers. He explored and uncovered facets of sound the way Picasso did with shape and color and Joyce did with language. He did all of this as his way of serving God and promoting civil rights.

Any single album of his puts him among the greatest jazz musicians. Blue Trane (1958), Giant Steps (1960), My Favorite Things (1961), his work with Miles Davis in the quintet or on Kind of Blue (1959), his apprenticeship with Thelonious Monk. Brilliant! And all of these examples predate his Impulse years.

Impulse Records is my favorite jazz label. It is so emblematic of the changing nature of jazz music in the sixties and Coltrane was its frontrunner. Every record they put out was a boutique item, with its orange and black design, gatefold center, and dramatic glossy cover photos. More importantly, it gave musicians who were interested in pushing jazz beyond what was typically accepted as popular or commercial. I do not mean to discount the significant contributions of other labels like Blue Note, Verve, Roulette, or even Columbia, but Impulse created an entire world unto itself in a way that few labels ever could. Its punk equivalent, in my mind, is Dischord Records.

Africa-Brass (1961), Impressions (1963), Live at Birdland (1964), A Love Supreme (1965), Meditations (1966). These albums, if listened to side-by-side, give a limited picture of the evolution that Coltrane went through during his tenure at Impulse. All of his albums, however, contain extraordinary playing. The pinnacle is, of course, A Love Supreme.

I know the “free jazz” years, basically from 1965 until his death in 1967, are challenging to listen to, but it is well worth it. The thing that might be hard to understand about Coltrane is the sometimes aggressive nature of his playing. It sounds angry. He overblows. It sometimes lacks shape or direction. The music sounds random, uncontrolled, and without form. All of this is intentional. It is pure expressionism; his last album is even called Expression (1967). If you listen to him in those terms you can begin to understand what he is saying a little better. It is like seeing a Jackson Pollock painting - it looks like a big random mess, but the more you look at it, the more you can see it take shape. It has a rhythm, an energy all its own. It is not pretty, it is not orderly. But neither is life. That doesn’t mean it can’t possess beauty.

Lesson: Seek the beautiful in the ugly. You will be surprised by what you might find.

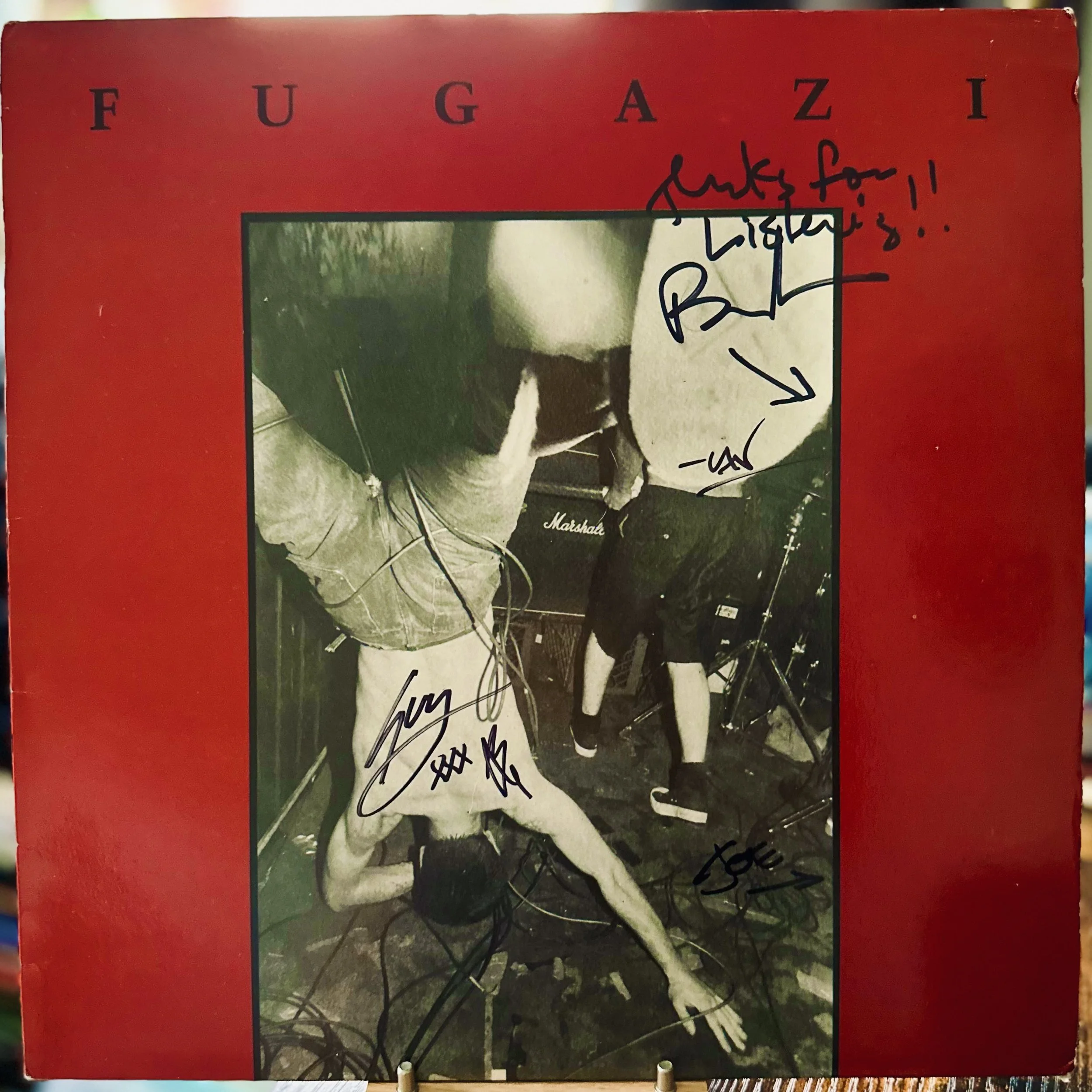

5. Fugazi

Fugazi has been a relatively recent obsession for me. I first heard them back in 2015 or thereabouts. I remember going record shopping with your Uncle Paul and stumbled across a copy of The Argument (2001). I recognized the band’s name as being a group that your Aunt Sarah was into back in the nineties, and I asked Paul if he knew them at all. Little did I know that he was a fanatical devotee.

I remember liking the music at first, but it took me a while to really get it. I got more of their albums, and my interest continued to grow. I also began digging a little deeper into the hardcore bands of the eighties that preceded Fugazi, especially those on Dischord Records like Minor Threat and Rites of Spring, along with others like Black Flag, Minutemen, and Dead Kennedys. Yet, it wasn’t until I watched the documentary Instrument that I fully began to appreciate what I had stumbled onto. What I saw was an example of a record label existing outside of the music industry. The music was made for the purpose of expression, not commodification. The real punk bands did not focus on making music that they thought people wanted to hear, or that they thought would sell. They made the music they wanted to make and wanted that music to be accessible to anyone who wanted to hear it. This applied to live shows as well as selling albums.

This realization flipped everything I thought I knew about music. It does not discount the great music that has been made for mainstream consumption. Hell, I could listen to Thriller (1982) every day for the rest of my life and not grow tired of it. It puts into perspective the accomplishments of great artists, like the Beatles or Dylan, who applied new and innovative techniques to popular songwriting and evolved pop into what we now consider “rock.” It doesn’t even prove the notion that pop punk bands (like Green Day for instance) are full of shit. It just frames the accomplishments of popular artists - musical or otherwise - as being conducted within the mainstream culture for the purpose of selling something.

Fugazi didn’t do that. They didn’t even say that doing that was necessarily bad, it just wasn’t them. They rejected lucrative offers to join major labels and tour professionally. They signed local bands and oversaw the recording, production, packaging, and distribution of their records. They created a model of DIY music that actually worked successfully (and continues to, to this day). This tapped into a long-dormant belief in my psyche that there are actually people out there who make music independent of the industry. I know the term “indie” is used too often; it sometimes carries about as much weight as “organic” does in a grocery store. But Fugazi was truly and authentically independent of the mainstream.

But ethos aside, the music is great. Like, really great. The lyrics are so eloquently written, the production is amazing, and the playing is so tight. I was really excited to learn about their writing process - the four of them jam, come up with riffs, piece together ideas, and put together cohesive ideas over time. Whoever brings in lyrics that fit the groove ends up singing them. But, otherwise, it is truly a rare democratic, collaborative process. Even Brendan, the drummer, brings in guitar riffs - and usually ones that prove challenging for the others to learn.

In short, Fugazi taught me what punk is really about, which helped put music into a more meaningful perspective. They drew the line between punk and MTV punk and helped me to better empathize with the trouble Kurt Cobain always spoke about with fame. Learning about the early hardcore days of the eighties and hearing the developments made in the post-hardcore days of the nineties helped me see how the greater political landscape of the country during this time shaped the music. And the music that existed outside of the MTV culture, through labels like Dischord, SST, Alternative Tentacles, Lookout!, SubPop, and others provides a more meaningful and accurate portrait of America.

One more thing you should know: they are really nice guys! Guys who show up to play, talk with fans, sell their own merch, and just treat people with respect. This is unheard of in the mainstream music industry. I got to see the Messthetics, which has two former members of the band, play a few times. Brendan Canty (drums) and Joe Lally (bass) have joined up with guitarist Anthony Pirog, and have put out several records. I went to see them with Paul before their first album was released. It was one of the greatest nights of my life! Seeing these guys, who I idolized - and speaking to them casually before and after their set in a dive bar in Brooklyn - this was almost too good to be real. Guy Picciotto (Fugazi’s guitarist and singer) was in attendance, as well. I had a copy of Fugazi’s first record with me and had the three of them sign it, which they did graciously.

This whole experience has set my life on a different path. No, I am not like a different person altogether, but I just see things a different way. Ian MacKaye was a kid who felt like other high schoolers pressuring him into drinking, smoking, and having sex was a load of bullshit, and he found punk music as an anchor, grounding him in something real, safe, and genuine. He played in bands and founded a label that gave other musicians a medium to create music that was true to themselves. It fostered community. It gave a voice to the underdog to speak out against social injustice and political corruption. It lets people know that if they reject the norm, and don’t follow others like a bunch of sheep, it is because they are strong, not weak. That is punk, and it’s a lesson that Fugazi taught me.

Lesson: Practice what you preach. Know what your values are, and live by them. In doing so, you are an example to others.

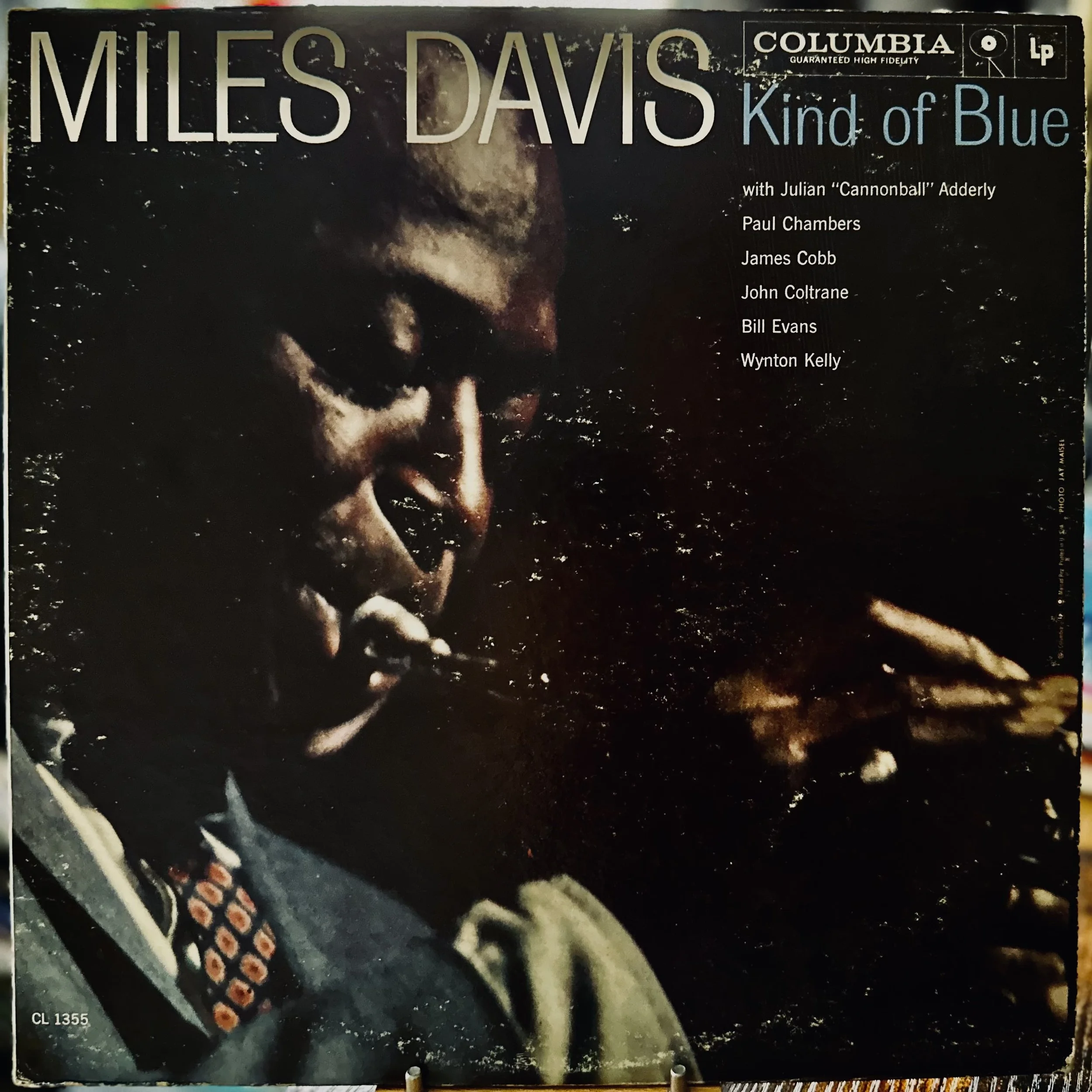

4. Miles Davis

He is not the best trumpeter, not by a long shot. But no other jazz musician has a catalog quite as profound as Miles Davis. For a career spanning half a century, the development his music took is unparalleled. His early recordings contain some fine playing but it is not until (in my opinion, at least) his first great quintet with John Coltrane that his genius begins to take shape. The group recorded several albums and played mostly standards, but what stands out about this group is how each player developed during that time, and the space Miles gave each to do so.

This early era culminates with Kind of Blue (1959), Miles’ adventures into the realm of modal jazz. This means that rather than play through a series of chords, the music stays on one chord for a longer period of time, which pushes the performer to improvise off scales (modes) related to that chord. It is closer in nature to Eastern music and was a significant turning point in jazz.

This album was particularly important to me - it was the first jazz album I ever listened to. I mean really listened to. I was listening to a radio marathon counting down the best 100 albums, and amongst the obligatory Dylan and Beatles albums at the top of the list was Kind of Blue. They played the entire record from start to finish, and I just sat and listened to it, not quite knowing what to expect. I was not interested in jazz until that moment, but from that moment on, the world of jazz was completely open to me. Or, more accurately, I was open to it. I began to listen to Miles, Coltrane, Thelonious Monk, Count Basie, Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy…the list goes on and on. Every album I heard opened me up to new players. It is like a tree that continues to grow and branch out. You hear one album, and really like the piano player, so you begin listening to albums by that guy. And so on. The genesis for me was Kind of Blue, and to this day it is still my favorite jazz record.

After that point, his direction changed. He eventually formed his second quintet with Wayne Shorter and Herbie Hancock, both of whom I have seen perform live. I even had the honor of meeting the bass player from this group, Ron Carter, at a jazz symposium I attended in college. The group’s compositions became looser, more explorative, and unlike any other group of the time. The music was the product of a collective mind, not a single one. Miles knew how to harvest the talent of younger players better than anybody else, and how to tap into their ideas to push his music into new directions.

He also began to transition to a more electronic sound, peaking with Bitches Brew, and later, On the Corner. After this point, for the first half of the seventies, his compositions became record-length explorations with insane tones and timbres. This is where a lot of people lose interest, but I love this period. Each of his albums is kind of like an impressionist sound painting. The notes flow in and out, and the colors shift and fade. There is no particular melody or form, it is just strokes of colors, sort of like in a dream. It reminds me of Monet, in a sense - it is not what life looks like, but what it feels like.

Lesson: Make sure everything you do leaves an impression.

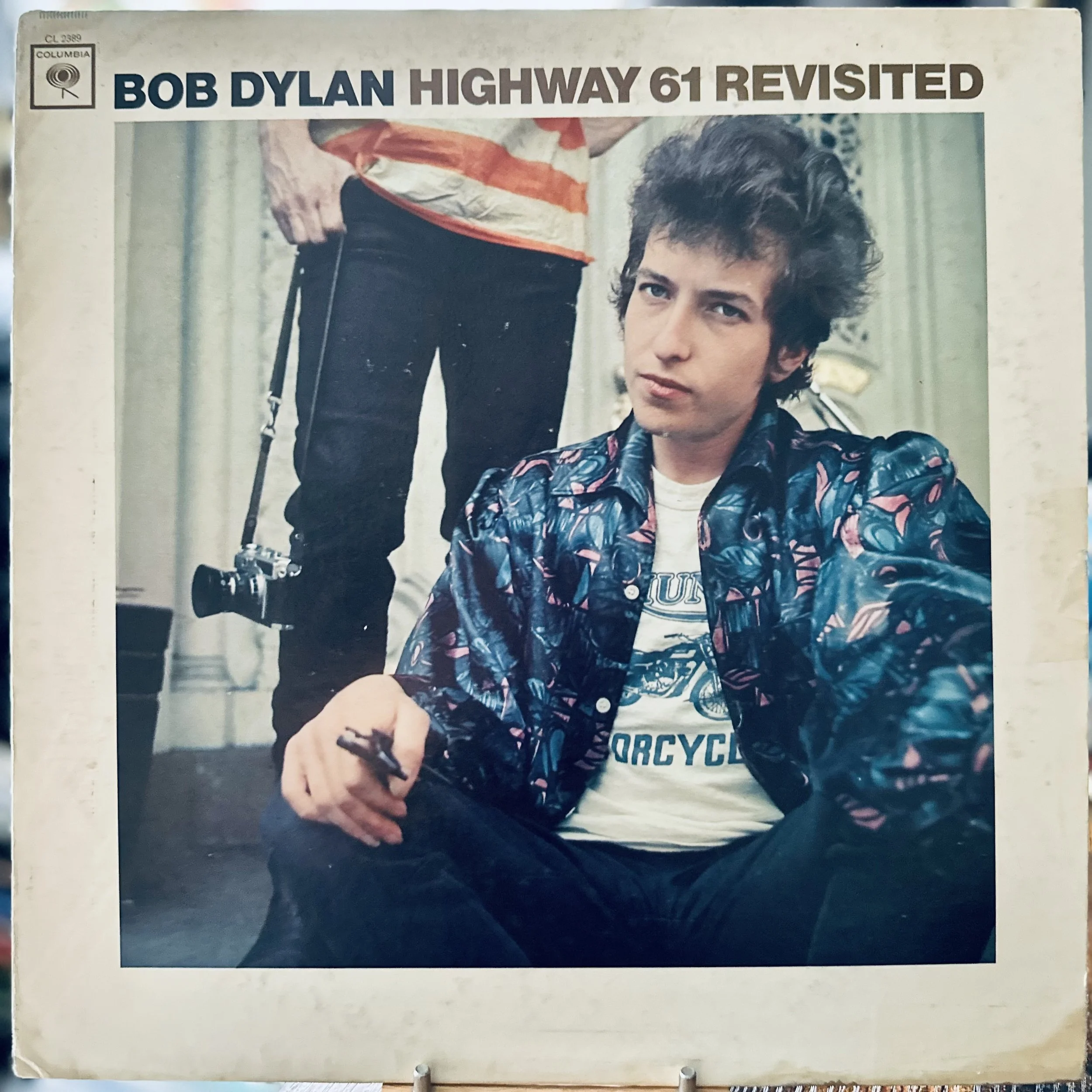

3. Bob Dylan

If any single individual has had an impact on my life via the creative process, it is Bob Dylan. After discovering the Beatles, Dylan seemed the next logical move. I think I began with listening to your grandfather’s records from the sixties, sorting through titles of songs that I seemed to recognize - “Blowing in the Wind,” “Mr. Tambourine Man,” “Like A Rolling Stone.” Before ever having listened to his music, I was aware of his work in the sense that a young child is aware of the name Shakespeare or Beethoven. It is a name of unquestioned genius, so deeply embedded in the cultural canon that it is simply accepted as such.

Your grandfather, who was a writer and student of English, listened to Dylan passionately in his youth but seemed to have lost interest during the seventies. He has most of Dylan’s records of the sixties, most of which were first mono pressings, and were kept in pristine condition - that is, until our cat urinated on all of them. I guess she wasn’t a fan. Eventually, I replaced all of these covers with better ones and gave each of my father’s vinyl records an appropriate home to inhabit. I likewise took care of the records of Leonard Cohen and Joni Mitchell from the same era, many of which suffered the same injury that fateful day my cat let us know how she felt about the singer-songwriter genre.

For me, Dylan is best understood within the context of his various eras. His work seems to naturally sort of fall into certain periods, at least in my mind, and a given song or album is usually best understood based on what came before it, and even what came later. The periods can be described as such:

Folk, 1960-1964. This is the earliest phase of his career, sometimes labeled as “protest music.” This term is somewhat problematic, but it does encapsulate the notion that Dylan stood on a side of a given issue. Some of his music was traditional (or arrangements thereof), and some were humorous or topical. He obviously drew from many sources in the folk tradition, but his brilliance was his ability to reconstruct and create his own statement within a given structure. His sense of rhyme, meter, and narrative was brilliant, especially for someone in their early 20s.

Folk Rock: 1965-1966. This is generally considered Dylan’s finest period. In 1964, he released Another Side of Bob Dylan which, while it contained no amplification, was closer in scope and style to Bringing It All Back Home than anything that came before it. It is a transitional album that sees Dylan moving away from the topical and satirical and closer to impressionism. He even goes so far as to dismiss his early work in which he preached and took sides, completely disowning the “protest” movement he supposedly led. His music, moving forward for quite a long time, was decidedly amoral, and often used words to express something deeply personal, or words for the sake of their own beauty and construction, rather than to send a message.

Americana: 1967-1973. After his motorcycle crash, he retreated and recorded the Basement Tapes with the Band in Woodstock, and later released John Wesley Harding, which is arguably his most underrated album. Never has someone used the three-verse/no-chorus format with such depth and imagination. He went on, after this, to explore country music, the American folk songbook, and ultimately returned to a more subdued version of himself on New Morning. This period’s output is kind of hit-or-miss, but as his numerous outtake-riddled releases have gone to show, the albums of this period had some substance but were ultimately troubled by poor production and song choice.

Rock Star: 1974 - 1978. This was another period marked by highs and lows for Dylan. It starts off strong with Planet Waves, a half-forgotten collaboration with the Band. It is overshadowed by the masterpiece that came next, Blood On The Tracks, which is easily his best album of the decade. Yet, fame had clearly gone to his head, marked by the over-blown singing and eccentric tours, and a decline in quality toward the end of the decade. It reminds me that he was still a rock star, one who was out to make money at the end of the day. He was, by this point, a commodity.

Born Again: 1979 - 1981. When Dylan turned to evangelical Christianity, the struggle, for me, is that he became so preachy. While it is true that he had always used Biblical imagery, it was never used to preach the word of God until this era. His relationship with the Bible before this era was like that of the Coen Brothers in O Brother, Where Art Thou? in that it was used as a device to connect to a tradition, and in doing so, gave larger meaning and depth to the story. Dylan’s Christian period is nothing like this - it is gospel music that one might imagine hearing during a TV broadcast from an evangelical tent.

Burnout: 1982 - 1996. This was a low point, in my opinion. To be honest, I haven’t actually heard much of the music from this era. But let’s face it, there is a reason for that. The same can be said about many of the other rock Gods of the sixties by the time they were middle-aged. Perhaps they tried to maintain something they no longer had, or tried to fill shoes that were no longer theirs. It happens. But, at the end of the day, I am not spending my time listening to this stuff. That said, between his Christian albums and this, there was a solid 20 year slump.

Renaissance: 1997 - present. Thank God. Time Out Of Mind (1997) was a turning point. It was like hearing Dylan be Dylan again, and he kept it coming. “Love and Theft” (2001) was actually a step up from there. The past quarter century has had its peaks and valleys, but it has been a strong output overall. What he succeeds in during this phase is what he succeeded in at the beginning - taking existing forms, words, phrases, ideas, etc., and re-crafting them into something new. It is like watching an artist take existing media and rework it into something unique. The idea that this is plagiarizing is wrong - this is what American folk, jazz, and popular songwriters have done since the pilgrims first landed. Would you accuse Andy Warhol of plagiarization because he used a photo of a soup can? He used an existing image and re-crafted it in a way that gave it new expression, meaning, and context to make it his own. Dylan does this with words and songs, and he does it brilliantly.

Lesson: No lesson here. Just listen to Bob Dylan. He is the greatest songwriter who ever lived, slumps notwithstanding (you can skip his stuff from the eighties).

2. Radiohead

The number two spot for me is Radiohead. I know that their music is challenging to listen to at times, and lots of people fall into the “before OK Computer (1997)” or “after OK Computer”. But there is much credit due to this band. Their longevity is impressive. Let us not forget that their debut album, Pablo Honey, was released in 1993. And while it is not my favorite of theirs, it is a brilliant album and is overshadowed by the success of work to come. Its follow-up, The Bends (1995), was a definite step forward. These two albums feature great lyrics and melodies, an unusual three-guitar front, impressive bass lines, and stellar production.

But OK Computer is the undisputed masterpiece of their 20th-century output. It is impressionistic in its sound, thematic in scope, and does not have a single poor track on it. I was impressed (though not surprised) to read that it was largely influenced by Bitches Brew. I have often felt that OK Computer was impressionistic, in a sense - the sounds are fluid and more felt than heard. The lyrics are figurative, with more feelings than thoughts. Had Radiohead broken up after this record, I am curious what their reputation would be. A three-album series of masterpieces from the 90s - they would have gone out on a high note, maybe without the mythologizing of Nirvana, but definitely in the same ballpark. I also love how Radiohead acts as a collective unit with additional personnel - producer Nigel Goodrich and artist Stanley Donwood. With OK Computer, their albums shift weight from just an album of music to an art exhibition. It was not about the group as individual personalities, but rather as a collective experience. The artwork is as much a part of the album as the music.

Then, the 21st century came. Kid A (2000) and its follow-up Amnesiac (2001) were recorded during the same sessions. I often wonder what it would have been like if it had been released as a double album. Instead, Amnesiac suffered the fate of a follow-up, always to be compared disfavorably to its older brother. In any event, both albums are brilliant. Employing the Dadaist technique, lyrics were randomly assorted with no narrative trace, but rather impressionistic visions. Electronic beats and loops formed the basis of backing tracks - gone was the three-guitar powerhouse. Software-generated vocal tracks, ambient noises faded in and out, and beautiful but chilling orchestrations penetrated the songs. The vocals are treated as just another instrument, not the foreground of the song. And there are other details that are often felt, but not heard. Take for instance the drumming on “Optimistic” - a repetitive pattern that is played over and over again, without a single crash of the cymbals until the very end. Without them, the tension builds without release - until, that is, the final repetition of the refrain, where it feels like a tidal wave comes rushing through.

Hail to the Thief (2003) was their last major label album. It was around this time that I began really getting into them. It felt pretty on the money for the politics of the time, and while it didn't pack the punch of Kid A, was definitely a strong record. After this record, we see Thom Yorke - solo artist emerge. The Eraser (2006) blew my mind with its electronic pops and fuzzy effects. Additionally, Johnny Greenwood scored the film There Will Be Blood (2007), which impacted me so much I wrote a paper on it for my Master’s Degree. It was hard not to take these guys seriously as artists, although I was scared they might be through as a band. Thankfully, they continued onwards while pursuing their own solo projects, including Atoms for Peace and the Smile.

As they released more albums, they created the model for what any musician of integrity hopes to do - self-release. They began as a major label act, found mainstream popularity, quickly dismissed it, changed directions, and then were free to release what they wanted and how they wanted when that contract ended. And, they had the balls to let fans name their own price. They continue to evolve because they don’t feel the need to sell records to a mass crowd anymore. God knows they will have the diehards (like me) that will buy every piece of music they create. The solo albums, soundtracks, and group efforts all continue in full force. Each has its own complete statement, both aural and visual. The music may be less catchy or direct, but it continues to send chills down the spine, and demands repeat listening to be fully understood.

In short, Radiohead is not just a group anymore. They are the fulfillment of the 21st century’s version of the composer. I mean, in the sense that Mozart or Beethoven were composers of “art music” or as we call it, “Classical.” Radiohead’s catalog is that - each album a symphony in and of itself. Sure, they are depressing, but they reflect back to us what they see in our culture, which music is supposed to do. And they do it with an intelligence and integrity that is unmatched in most musicians.

The lesson: Music can be experienced cohesively as a complete piece of work that appeals to multiple senses; just because it is not classical, does not mean it is not highly valuable or has artistic merit.

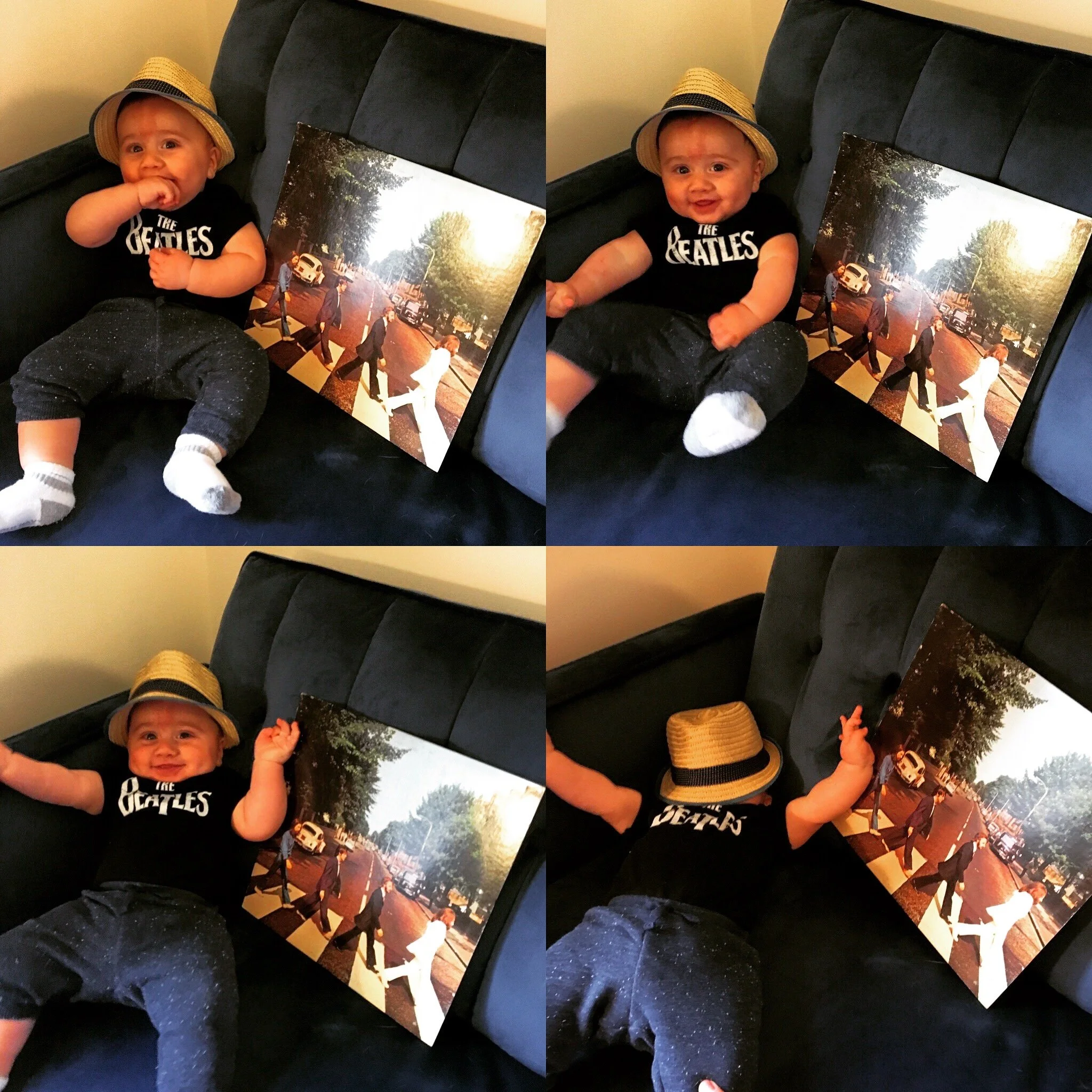

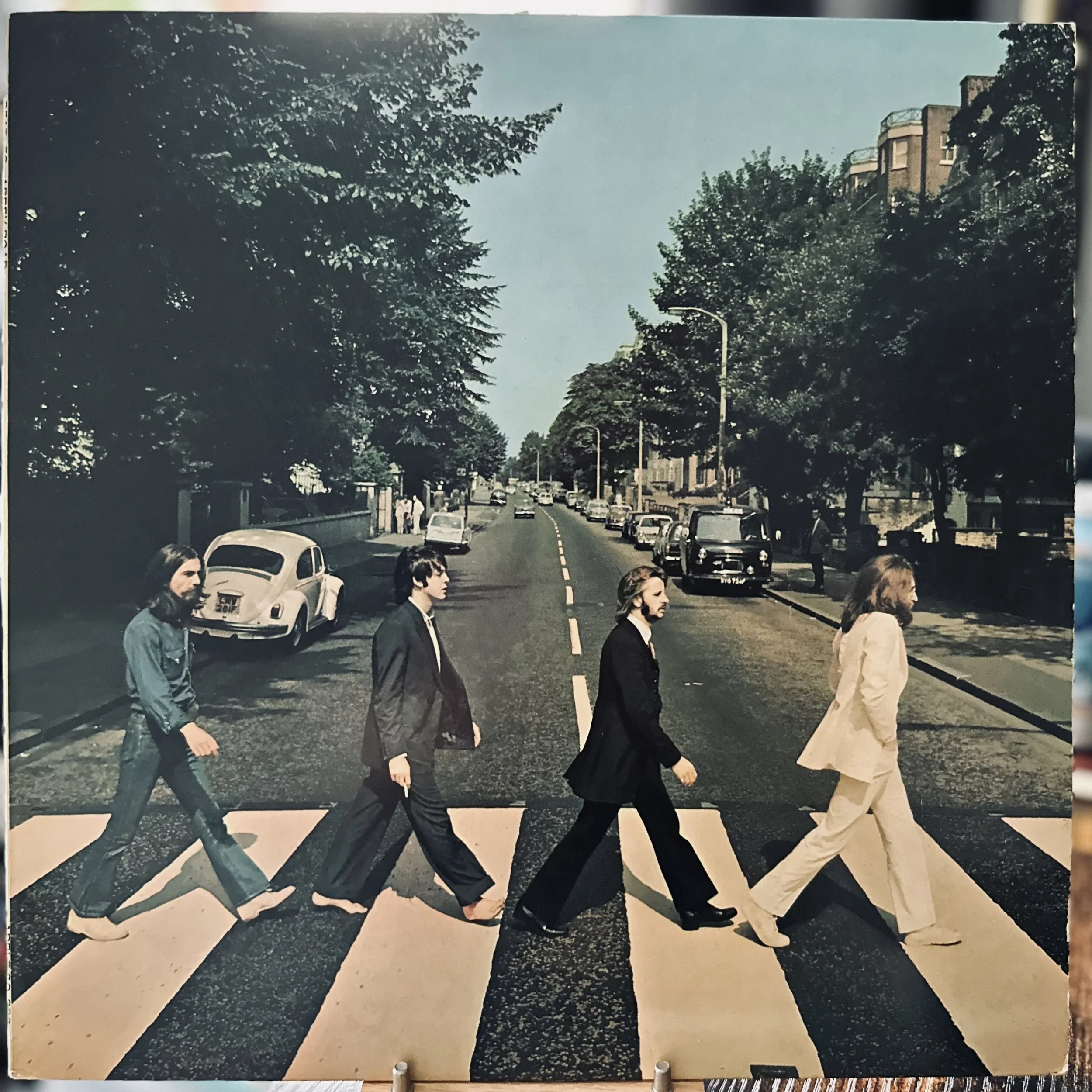

1. The Beatles

I will be honest with you, Harrison - I have dreaded writing this section. I cannot put into words what the music of the Beatles has done for me. I have been obsessed with them for over thirty years - hell, you are even named after one of them. Volumes have been written about the group: how they changed music, how they evolved from album to album, and how they elevated rock to an art form. I don’t need to write about that here. What I do want to do is attempt to give you a brief breakdown of their best albums. It is largely an arbitrary exercise, but let’s give it a try:

My favorite album: Abbey Road (1969). This was the first one I heard, so it struck the deepest chord in my soul. It also is the culmination of all that they were capable of as a unit. It is impressive, given that the entire second side basically follows symphonic form.

Their greatest album: Revolver (1966). This album was the height of their creative energies and experimentation with studio techniques. They expanded beyond the guitar-driven rock song while keeping the music accessible.

Their underrated album: A Hard Day’s Night (1964). There is not one bad song on this album. Yeah, it is still their boy-band Beatlemania phase, but it is damned good songwriting that still rocks. And it is notable as being the first (and only) album written entirely by Lennon/McCartney, marking a shift of the pop musician who regurgitates popular music to the rock star who creates new music.

My sleeper favorite: Rubber Soul (1965). This was a giant leap forward, and while it is not as experimental as their later work, contains multitudes of complexities that are still organic and lovely.

Their magnum opus: The White Album (1968). It is an epic effort, for obvious reasons - it is a sprawling mosaic that never gets tiring to experience.

Their masterpiece: Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. It is a cohesive work that shifted the rock genre from emphasizing the single/song to the album as a cohesive artistic statement.

So there you have it. You need to listen to all their music, though. Even the deep tracks and outtakes, it is all worth hearing. If Beethoven had a tape recorder and recorded himself, it would be just as valuable.

Lesson: All you need is love. And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.

I hope this list gives you a little insight into who I am, where I come from, and what I believe. Now, go make your own list.

Addendum: The 101 Greatest Records I Have Ever Heard

While this is mostly an arbitrary task, I wanted to challenge myself with a thought experiment. This list below is not “my favorite albums” or my “desert island discs.” It is 101 of the greatest records I have ever heard in my life. This means that having scanned through my collection of thousands of albums, I have narrowed down the ones that I consider to be the greatest.\

I think what is more telling than the albums included here are the ones that are not included. There is a psychological process involved that labels certain albums as “having to be on this list” that cannot be excluded. However, I also tried to avoid the trap of only listing albums by my very favorite artists. Such a list would be too narrow in scope. Bearing that in mind, I have set the following constraints for this list:

No more than five albums by a single artist (The Beatles and Dylan have that distinction)

No greatest hits, soundtracks, or compilations - the content must have been conceived of as an album by the artist

Live albums are included only if they were released as an “album” within the standardized canon of a band and not a later compilation or collection (the Grateful Dead’s Europe ‘72 is included, but Coltrane’s The Complete Live at the Village Vanguard 1961 boxed set is not)

I think there is also a nostalgic component, as well - I often feel more connection to the first album I heard by an artist or a memory I associate with it, rather than an objective lens of which album is better written or constructed. For example - is Blonde on Blonde better than Highway 61 Revisited? Probably - it is a more complex effort, a far-reaching achievement; yet, Highway 61 was my entry point for Bob Dylan, and will always be my favorite. I try to defer to my gut feeling rather than an intellectual argument.

But, as I said, the omissions in the list are glaring. The Cure is not represented, nor is Thelonious Monk. No contributions from Eric Clapton, one of my favorite guitarists, or New Order, one of my favorite bands. No PJ Harvey, Kate Bush, Minutemen, or Black Flag. At the end of the day, if I had to choose between, say my fifth favorite Beatles album and my very very favorite Clapton album, I opted for the Beatles. If this is a fair choice is debatable, but it is the mindset I used, and thus representative of my point of view. With that lens in mind, this list is truly my list. Please forgive the glaring omissions.

So here is my list, prioritized from 1 to 101, of the greatest albums I have ever heard in my life. Thus far, that is. Who knows what kind of list I will produce a year from now, ten years from now, or even next week, for that matter? That is the fun part - it is more of a snapshot into my mind and a statement of my values, for better or worse.

Abbey Road - The Beatles

Highway 61 Revisited - Bob Dylan

Bach: The Goldberg Variations (1955) - Glenn Gould

Kind of Blue - Miles Davis

Revolver - The Beatles

Kid A - Radiohead

Bach: Cello Suites - Pablo Casals

Blonde on Blonde - Bob Dylan

Low - David Bowie

Whiskey Before Breakfast - Norman Blake

Beethoven: Symphony No. 9 - von Karajan / Berlin Philharmoniker

A Love Supreme - John Coltrane

The Argument - Fugazi

Electric Ladyland - The Jimi Hendrix Experience

American Beauty - The Grateful Dead

Fear Of Music - Talking Heads

The Queen Is Dead - The Smiths

Blues And The Abstract Truth - Oliver Nelson

Zombie - Fela Kuti

Thriller - Michael Jackson

The Man Machine - Kraftwerk

The Beatles (aka “White Album”) - The Beatles

Bitches Brew - Miles Davis

Beggars Banquet - The Rolling Stones

Wish You Were Here - Pink Floyd

Station To Station - David Bowie

In On The Kill Taker - Fugazi

Unknown Pleasures - Joy Division

All Things Must Pass - George Harrison

Innervisions - Stevie Wonder

Shostakovich: Symphony No. 5 - Bernstein / NY Philharmonic

Led Zeppelin IV (aka Untitled) - Led Zeppelin

Study In Brown - Clifford Brown & Max Roach

This Year’s Model - Elvis Costello

In Utero - Nirvana

Blackstar - David Bowie

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band - The Beatles

A Charlie Brown Christmas - Vince Guaraldi

Meat Is Murder - The Smiths

Remain In Light - Talking Heads

Forever Changes - Love

OK Computer - Radiohead

Under The Iron Sea - Keane

The Velvet Underground And Nico - The Velvet Underground

Out To Lunch - Eric Dolphy

Tommy - The Who

Everybody Knows This Is Nowhere - Neil Young & Crazy Horse

Dvorak / Tchaikovsky / Borodin: String Quartets - The Emerson String Quartet

The Rise And Fall Of Ziggy Stardust And The Spiders From Mars - David Bowie

Europe ‘72 - The Grateful Dead

Computer World - Kraftwerk

The Downward Spiral - Nine Inch Nails

Tago Mago - CAN

Chicago Transit Authority - Chicago

LA Woman - The Doors

Transformer - Lou Reed

MTV Unplugged In New York - Nirvana

Rubber Soul - The Beatles

Songs Of Love And Hate - Leonard Cohen

Bringing It All Back Home - Bob Dylan

Expensive Shit - Fela Kuti

Dark Side Of The Moon - Pink Floyd

Live At Leeds - The Who

On The Corner - Miles Davis

Let It Bleed - The Rolling Stones

John Wesley Harding - Bob Dylan

Horses - Patti Smith

Beethoven: Symphonies No. 5 & 7 - Kleiber / Wiener Philharmoniker

Songs In The Key Of Life - Stevie Wonder

April In Paris - The Count Basie Orchestra

Church Street Blues - Tony Rice

The Stooges - The Stooges

13 Songs - Fugazi

Meditations - John Coltrane

Closer - Joy Division

Aqualung - Jethro Tull

Nevermind - Nirvana

Animals - Pink Floyd

The Shape Of Jazz To Come - Ornette Coleman

Hitchhiker - Neil Young

Blood On The Tracks - Bob Dylan

The Wall - Pink Floyd

Here To Stay - Freddie Hubbard

The Idiot - Iggy Pop

The Allman Brothers At The Fillmore East - The Allman Brothers

Bartok: Concerto for Orchestra / Music for Strings, Percussion, And Celesta - Reiner/CSO

Come Swing With Me - Beverly Kenney

The Stranger - Billy Joel

Houses Of The Holy - Led Zeppelin

Fresh Fruit For Rotting Vegetables - Dead Kennedys

Quah - Jorma Kaukonen

Out Of Step - Minor Threat

The Score - The Fugees

At Folsom Prison - Johnny Cash

Combat Rock - The Clash

Harlem Street Singer - Rev. Gary Davis

Pet Sounds - The Beach Boys

Berlin - Lou Reed

The Awakening - Ahmad Jamal Trio

The Fragile - Nine Inch Nails

The Black Saint And The Sinner Lady – Charles Mingus